A sobering thought

A sobering thought

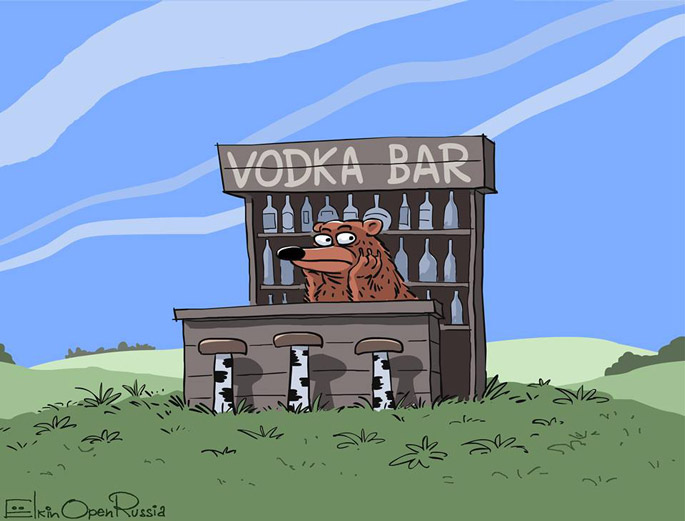

It sounds like something you’d make a joke about – the West is drinking much less Russian vodka. But it’s a sobering thought.

Exports of vodka from Russia declined by more than 40% in 2015. In value terms they fell to $111.9 million, which is 40.2% less than in 2014 ($187.1 million); and physical volumes fell by about 42% to 4.35 million decalitres – a return to the figures of 2005. Why they have fallen so steeply tells us much about what has been happening to business in Russia, and the effect of geopolitics.

Vadim Drobiz, director of the Research Centre of Federal and Regional Alcohol Markets, which compiled the figures, says that the economic crisis in the country means small and medium businesses can no longer export their goods. “Promoting one’s product in the West is very expensive, something that only large, strong companies can afford, and these are the companies that are still in the market. Smaller companies only started exporting to compensate for their losses in the domestic market, when prices for legal vodka soared by 250% after the 2012 excise reforms, and consumers started buying bootleg vodka.” He sees political factors at work also. “Because of the events in Ukraine and Syria, the West’s attitude to Russia has deteriorated, which may be the main reason for the decline of Russian vodka sales.” Which suggests that there may be a subconscious factor at work here: when the barman asks what vodka you want, the Westerner opts for Swedish, Finnish, Polish …

The figures speak for themselves.

In any case, Drobiz says that exports of Russian vodka represent such a small percentage of the world vodka market “as to be virtually imperceptible.” On the whole, the world drinks non-Russian vodka – British Smirnoff, Swedish Absolut etc. Even the legendary Soviet Stolichnaya, the foreign rights for which Russia has been trying to get back for the last 15 years, is now produced by the SPI Group in Latvia. He is not at all sure that the share of the market freed up by Russia will be of interest to any of the big players. “A 40% decline in Russian volumes is only 20 million litres. This is a drop in the ocean and it’s not a given that anyone will be rushing to fill that gap.”

That view is supported by Mikhail Smirnoff, editor-in-chief of the alcohol.ru portal. He also thinks the world will easily cope with any reduction in Russian vodka supplies, and that the main problem is at home, not abroad. “Our vodka exports are minute – only 1.5 to 2% of total production. High prices and fewer shops have meant that 60% of spirits on sale in Russia are counterfeit. We are in the middle of an alcohol crisis.”

But there is another story here. Look through that open wall, and you understand that those insignificant export streams are of no interest to the people who control the production and sale of vodka in Russia. People like Arkady Rotenberg, billionaire friend of the president, who is one of the biggest players in the Russian alcohol market.

Vodka, like so much else, is yet one more example of the way in which business, over the past fifteen years, continues in the age-old way: the distribution and re-distribution of assets. Firstly, to satisfy his passion for monopolising everything, in the early 2000s Putin set up the quasi-commercial Rosspirtprom, to consolidate Russian spirit assets. Then, quite a number of those assets went to the president’s childhood friends.

A key function in the re-distribution of distilleries was meanwhile handed to the Federal Service for Regulating the Alcohol Market (RAR, in Russian). This supervisory government department has almost unlimited powers, and can turn a successful private vodka distillery into something rather less so in a very short period of time.

The method is a tried and tested one. The owner of the distillery receives an offer to purchase his business – an offer he cannot refuse. If he should protest, and not be amenable, then RAR is brought in. Inspectors are sent to check over the business, which is refused the necessary excise stamp, and sometimes has its licence withdrawn all together. End of business.

For those few vodka businessmen who have survived, and looked to the West to keep their businesses alive, it is quite likely that they have been let down by their marketing and advertising campaigns. They almost all tried to emphasise how Russian both they themselves and their product were. Today, after the annexation of Crimea and the events in Eastern Ukraine, these associations, once such an advantage in dealing with the competition, have only caused additional problems.

The Siberian Alcohol Group, an active exporter, has noticed that foreign partners have recently behaved differently with Russian suppliers. “They are afraid to expand the range of our goods because they think the demand for Russian vodka may fall off, or new sanctions could be introduced.”

Without active government intervention to assist with export, Russia’s international vodka business is today essentially non-viable. As the spokesman for Siberian Alcohol Group explains, “Alcohol is part of a country’s image, and needs enormous injections of finance. For countries exporting alcohol, e.g. Great Britain, France and Italy, coordinated economic programmes are a priority. We don’t as yet have any. We have oil and gas so no one is interested in promoting other products.”

Mikhail Smirnoff agrees. “Government support is essential. Without it, Russian vodka will continue to be sold as it was previously – as an exotic present – where we could have been sending shedloads of it. We need targeted programmes. Our planes are promoted on the international military market, and that’s how we should be promoting our vodka.”

Na zdorovye.