Bourgeois, imperialist and capitalist

Bourgeois, imperialist and capitalist

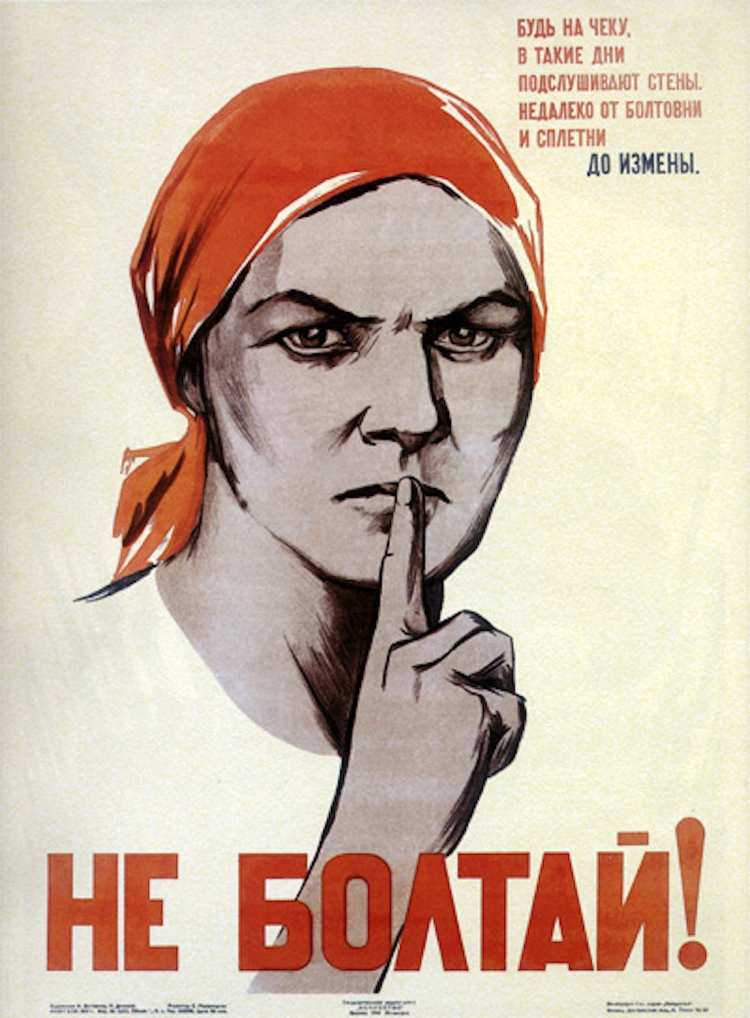

Modern Russian propaganda is often compared to its Soviet forerunner, and not without reason: the turns of phrase of pro-Kremlin TV commentators and newspaper columnists directly mimic Soviet brickbats.

The old Soviet rhetoric about the proletarian revolution has been scaled back, as have the “bourgeois,” “imperialist” and “capitalist” epithets, since Russia itself is now all of the above. And communist ideals have been supplanted by vague, gooey simulacra about traditional values and the like. But that aside, it’s all familiar territory: from the words about “traitors” and “fifth columns” to the charges of “anti-state activities” (read: dislike of the current government).

There is, however, one significant difference between today and the Soviet invective of the 1970s-80s. The propaganda back then was stronger and weightier than it is now. The only independent press to speak of existed in the form of illegally distributed samizdat and manuscripts. There was no official or non-systemic opposition, save for pitiful groups of dissidents who were often sent for psychiatric treatment. But despite all this, the propaganda effect was not only weaker, but often counter-productive. The more it lashed out at the West, the more Soviet society became fascinated by it. As people quipped at the time: the West may be “rotting” (the word used in official propaganda), but the smell is still quite pleasant.

But something has happened: now that 25 years have passed since the borders opened, tens of millions of Russians have travelled abroad, foreigners have ceased to be a rarity in Moscow, St Petersburg and other urban centres, Western brands have become ubiquitous, and two generations have grown up on Hollywood films and American comics – and the propaganda has suddenly hit the target. It strikes a chord with many in Russia, and not only elderly people brought up to fear “NATO aggression.” There are quite a few young believers too.

Why the sudden propaganda breakthrough? Has the Kremlin mastered some secret brainwashing techniques, or has the Russian mindset changed over the past quarter century?

There has been some change, for sure. By the time of Gorbachev’s perestroika, 300 million Soviet citizens nurtured naive, childish notions of capitalist countries as paradise on earth, where rivers of milk flowed between honeyed shores and (more importantly) any tiny shop boasted hundreds of varieties of sausage. All this went hand in hand with the idea that the transition to democracy and a market economy would be quick and painless, and that civil society would generate itself (it transpired that grassroots institutions, as the name suggests, have to be built from the bottom up, and the transition can take decades).

The nineties were not only a time of hope and opportunity, but one of tremendous disillusionment. The West failed in its role as Good Samaritan, while Russia’s new capitalist paradise produced gangsters, prostitutes and poverty galore. Democracy was no longer equated with happiness, but with the triumph of oligarchs and corrupt journalists, not to mention low wages for state employees (there is no direct logical connection here, but the stereotype of the “wild nineties” implies an indirect link).

A little later we saw a collateral effect, in many ways psychologically defensive. The middle classes who had visited, studied and lived in Europe and America came to the conclusion that the West is not as great as everyone thought. It’s all pretty much the same as back home – worse in some respects. Bribes and kickbacks exist there too, and everything grinds to a halt when it snows. The attempt to paint the West as less holy than “we ourselves thought” became an obsession. So when today’s Kremlin propagandists say that Western democracy is a sham and freedom of speech is fake, they are believed because people want to hear it. The public wants to be deceived.

As a postscript, and for the sake of fairness, it should be noted that Russian propagandists are ably assisted by Western journalists who demonise Putin (quite literally, on the cover of The Economist), or accuse Russian hackers of dirty tricks. The average Russian citizen sees this not as proof that his country is an outcast, but as a signal to unite around a national leader. Sadly, no one seems to understand this.