Cycle lanes in the concentration camp

Cycle lanes in the concentration camp

The Mayor of Moscow is all in favour of showing that Putinism has a millennial face. But for some reason, while it means more bicycles, it doesn’t include trolleybuses.

In Moscow some years ago, the so-called “Theory of Small Deeds” [originally a liberal-populist idea of the 1880s] was extremely popular. As Alexandra Boyarskaya expressed it in one of Afisha magazine’s manifestos, it was basically a way of convincing us in the here and now that we (predominantly young intellectuals – Moscow’s new bohemian set, which moved freely in and out of the liberal community) were already living in the West. No need to go to New York, London or Paris; all that had to be done was to open a few trendy cafes, shops and galleries here at home, refurbish an old warehouse, dress down and dream up some kind of new rationale for everything that we knew wasn’t quite right.

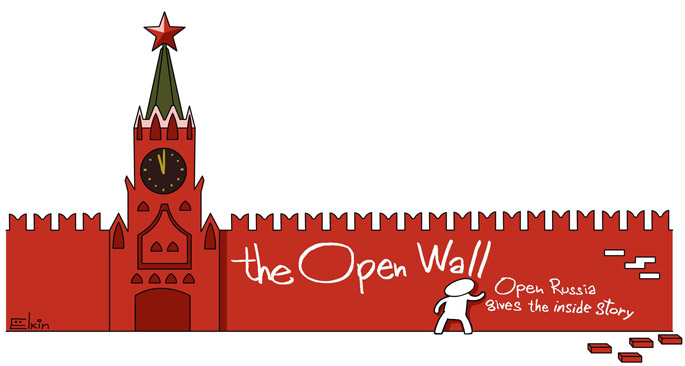

The more sceptically inclined – most of us – maliciously dubbed this approach “cycle lanes in the concentration camp,” meaning that calls to just get on with cultivating one’s own garden, and waiting for all the rest to miraculously fall into place, were simply a way of shutting one’s eyes to the bigger picture: falsifications, justice delivered by telephone call rather than the courts, censorship and political prisoners.

The “cycle lanes” period in the capital had two front men, hailing from two Moscow city departments: Culture, headed by Sergei Kapkov, and Transport, headed by Maxim Liksutov. When Kapkov left (or was removed as a deferred punishment for the fact that the “hippies” at the mayoral election of 2013 had preferred Navalny to Sobyanin), and his culture reform team was sent to make improvements to the city of Kazan, only Liksutov remained. Symbolically, it is now he who is letting the air out of the tyres.

Had it not been for some passionate activists under the leadership of Maxim Katz, municipal deputy from the Shchukino district, Muscovites would have had little chance of discovering that the Moscow city government was intending to do away with all the city’s trolleybuses, whose routes are spread out over an area of many kilometres, the biggest network in Europe.

Informed rumours suggest that this was a personal initiative of Mayor Sobyanin, who was clearly intending to do it all on the quiet: Muscovites would simply have woken up one morning to find that all the wires had disappeared, and the trolleybus stops were being serviced by diesel buses.

The past few weeks have seen a public campaign: open letters to Sobyanin (there was even one from Mosgortrans – the state-owned company operating bus, tram and trolleybus networks in Moscow and the surrounding region – which must be a first!), pickets, fundraising for advertisements on the radio and in the street, internet petitions. You would have thought that we were in Berlin … This has all been successful to the extent that the plan has been put on hold for the moment, but it may be too early to gloat – the city authorities may simply be waiting for the fuss to die down so that they can carry on with their plan.

It is, of course, not really just about the noiseless, electrical (and so much more environmentally friendly than diesel) trolleybuses, which have become the city’s hallmark, and are so dear to Muscovite hearts (Sobyanin is from Siberia, so he doesn’t get it). It’s really more to do with the fact that there was no consultation, and, like criminals, they were planning on doing it all under the cover of night.

What happened to those buzzwords like “electronic government” and “the system of direct democracy” promoted by the Moscow city government app “Active Citizen”? Nothing, apparently, because millennial authoritarianism is actually no different from any other kind of authoritarianism: it does what it considers right with no thought for anyone else. Everything else is, unfortunately, just a façade to cover up the unsavoury nature of this government.

But this certainly does not mean that cycle lanes, food markets, studios for young artists, temporary wooden architecture, and contemporary parks are harmful. Not at all – gentrification is a positive phenomenon: people in the spiritual dark hole of 2016 are carrying on with their small deeds, and not just in Moscow, but in Petersburg, Kazan, Nizhny Novgorod, Yekaterinburg, Novosibirsk, which is just great. Doing something is always better than doing nothing.

Just one thing, however: let’s not allow ourselves to be swayed by the false idea that this will somehow be enough to make Russia a flourishing European democracy. It won’t because we need to battle for politics as well as for aesthetics. Nothing will happen if we don’t have proper, working institutions, open elections, an impartial judiciary and a free press. Until then, we can all cycle around the concentration camp, dreaming of the Meatpacking District.