‘Everyone’s sentence is the same – as long as Putin is in power‘

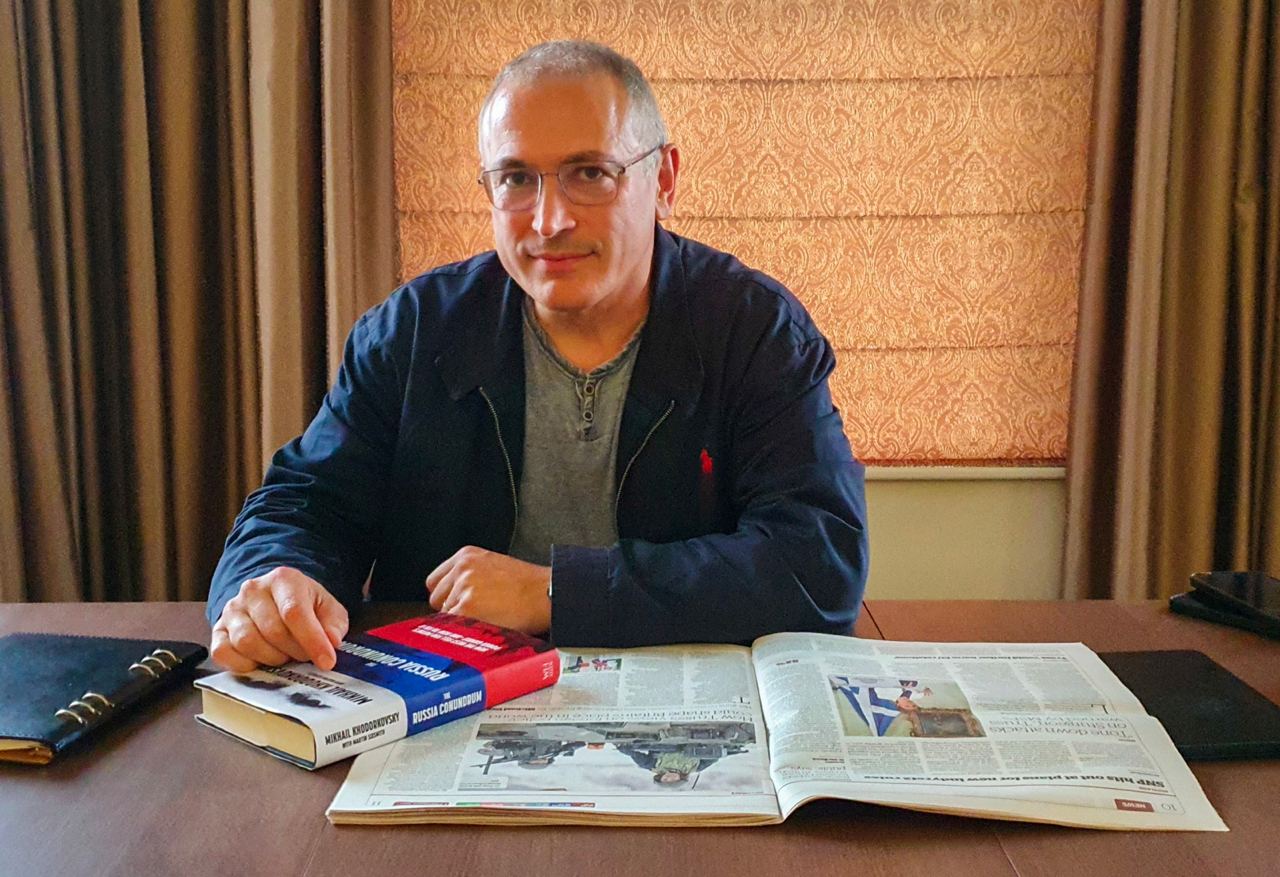

Mikhail Khodorkovsky on how to survive a prison sentence that only seems to grow longer

by Mira Livadina

On 4 August, a Moscow court found Russian politician Alexey Navalny guilty of multiple charges of extremism and reportedly handed him an additional 19-year sentence to be served after the nine-year sentence he is currently serving is over.

The strategy of gradually increasing prison terms by pressing new charges is not new to the Russian authorities. Back in the mid-2000s, the Yukos case progressed along similar lines. The moral aspect of this strategy is the hardest to bear: faced with more and more sentences, a person can easily give up on any belief in the future. Under such conditions, is it possible not to lose heart and to keep seeing the situation for what it is? This is the question Novaya Gazeta Europe posed to Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the Russian businessman turned exiled politician who spent 10 years behind bars after falling foul of the Kremlin. Given the Russian regime’s fondness for imprisoning its own citizens, many may find Khodorkovsky’s recommendations useful.

In 2003, I quite consciously went to jail. It sounds strange, but there was simply no other choice for me at that time — I either lost all self-respect or went to prison. So when I decided to return to Russia in the summer of 2003, I knew that my arrest was only a matter of time.

But what I honestly did not realise then was how lengthy my sentence would be. I was returning to my country to prove my innocence to myself, to my friends and colleagues. The courtroom was well suited for this purpose.

After all, for many people, escaping — and, I could have stayed abroad — meant that I would be admitting my guilt and making Yukos employees doubt the integrity of all the work they had done for years. At first, I was sentenced to nine years in jail. That term was then reduced to eight years, then increased to 14, finally stopping at 13 years, of which I served 10 years and two months.

That’s why Putin’s reprisals are so devious — you do not get your final sentence right away. You never know how long you really have left.

It’s hard. Very hard. You’re not just deprived of physical freedom — you’re deprived of any control over your life. This breaks many people’s willpower, which is exactly what the system wants.

Over time, I developed — partly intentionally, partly intuitively — a way of surviving in that situation. I have always loved to work. For me, business had long since become not just a way of earning money, but a path to fulfilment. That’s why I always worked more than I rested.

So I told myself that this was simply what my office looked like now — with bunks, bars, and bare concrete walls. But that doesn’t really affect productivity, does it? Sure, communication is difficult and there’s no computer, but I have time and the opportunity to concentrate. I started to read more history and philosophy, and to write much more than I had done before my imprisonment.

In effect, I began living by the maxim of “do what you have to do, come what may”. There were many things I couldn’t do, but I could do what I had to.

It was hard but necessary work. It allowed me to preserve my identity and even to prepare for the next stage of my life. During my imprisonment and two trials, I received a good legal education, learnt to write well, and became rather well-versed in the humanities, which is much needed nowadays.

Of course, there were times when it was quite bad, when I felt like the situation would last forever or when I found out that my relatives were in trouble.

Despair would strike when [businessman and Khodorkovsky’s close associate] Platon Lebedev was put in a punishment cell and threatened with never leaving it. When [former Executive Vice President of Yukos] Vasily Aleksanyan was tortured. When NTV showed news stories about the destruction of Yukos.

The hardest thing is to see the suffering of friends and family, knowing that you are the reason they are being tortured and not being able to do anything about it.

In such extreme moments, I used the last currency I had — my life. I went on hunger strikes, two of them without water, with the full understanding that I would either help my family or only have seven or eight days to live. And it worked. I won. However, I wouldn’t advise using this method unless absolutely necessary. Because if it doesn’t work out, you will die.

Now, other political prisoners are following my path: Vladimir Kara-Murza, Alexey Navalny, Lilia Chanysheva, Andrey Pivovarov, Ilya Yashin, and others. The prison terms are draconian — Vladimir has been sentenced to 25 years in jail, and Alexey faces 20 years behind bars. It’s very hard. The hopelessness of it crushes you and destroys you psychologically.

But in truth, everyone has the same sentence — “for as long as Putin is in power”. And we all have to strive to reduce this prison term — and we are doing so. Those who are free are doing everything they can to bring about regime change. And those who are temporarily behind bars have to preserve themselves. What helped me keep going was working hard and having a purpose.

The article was originally published in Novaya Gazeta Europe