How to get rid of Putin — and avoid another dictator in Russia

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the businessman turned activist, says Russia’s systemic sickness is rooted in its vast size, and power must be decentralised as a first step

Interview by Thomas W. Hodgkinson

A few days before we meet, a friend of Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s plunges to his death from a tenth-floor apartment in Moscow. It’s the latest in a series of untimely ends that, over the past two decades, have befallen prominent Russians, some of whom have opposed Vladimir Putin.

The autocratic president’s No 1 enemy, it has been said, is Khodorkovsky himself, once Russia’s richest man, who later came into spectacular conflict with Putin and then spent a decade in prison.

Did Mikhail Rogachev — a former vice-president of Yukos, the oil conglomerate that Khodorkovsky built in the 1990s — have cancer, as the Russian media reported, suggesting he took his own life? Khodorkovsky, who speaks to us in his central London headquarters, has his doubts. “His wife told me it was nonsense. And that got me suspicious, because someone started that rumour.”

Rogachev was “very clever”, and obsessed with “the depths of science”, he says. “If life had turned out differently, he would have worked at your institute.”

Khodorkovsky is referring to the London Institute for Mathematical Sciences, which runs a programme of fellowships for scientists affected by the war in Ukraine. This has been built upon and bolstered by support from the Khodorkovsky Foundation: the organisation the businessman-turned-activist created to promote learning in Russia and advance the development of civil society.

Since the spring of 2022, the institute has received hundreds of applications from Russians and Ukrainians. It has welcomed ten, including a member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the Russian equivalent of the Royal Society. They exemplify a peculiar gift for basic science — the kind that is not focused on applications but instead seeks out new

fundamental principles. Khodorkovsky believes that this proclivity has its roots in the Soviet era. “Back then, humanities subjects were under party control. Business was forbidden. Politics was practically non-existent. So the cleverest people had a narrow choice. Going into science provided freedom. If you were doing mathematics, then you could do anything you wanted.”

Some western organisations, most recently Cern, have moved to close down collaborations with Russian scientists. This is a big mistake, says Khodorkovsky. “If in the 1930s the United States had announced the same type of sanctions, it would not have seen the nuclear bomb so soon.” Nor, for that matter, the rocket technology that led to the space programme and moon landing.

The West should seek to “attract talent from Putin’s Russia. It’s not enough just to say that we provide opportunities through talent visas. Scientists should be sought proactively.” There are three reasons for this. “It’s good for the scientists — not to lose their best years, but to be involved in what they love. It’s good for western countries to accept clever people. I don’t know of any country with too many clever people. And it’s important to reduce Putin’s ability to conduct the war.”

As a child, Khodorkovsky was in love with space. He even built his own rocket which he launched on a street appropriately named Rocket Boulevard. By his own account, he completed three degrees: in law, public administration and engineering, during which he took a special interest in explosives.

He draws on all three areas of expertise in his recent book How to Slay a Dragon, an intelligent and scrupulous blueprint for regime change in Russia. The dragon in question, of course, is Putin, whom the author at one point compares to Donald Trump, on the grounds that both are opportunists with no deep political beliefs.

“But there’s also a key difference between the two men,” Khodorkovsky writes. “Putin is from the intelligence services. In any situation, he sees threats. Only later does he look for opportunities. Trump is an entrepreneur. He sees the opportunities but he ignores the threats.” What might be the consequence of another Trump presidency? He plays it down on the basis of the structure of American government. “The US is a big country with big governmental machinery. Trump can be doing something in one area. Everything else will be handled by his team, who are normal Republicans.”

This is by contrast with Russia, where the Putin effect is felt in every area of government, not only at home but also in neighbouring countries. Electoral victory in Georgia, for example, has just been seized by the populist Georgian Dream party, which is bankrolled by another former oligarch, Bidzina Ivanishvili. “I know him very well. He had the neighbouring bank to my bank, Menatep. His bank was called Russian Credit.” Khodorkovsky smiles, adjusting his rimless spectacles. “Which is funny. Ivanishvili is not about democracy. I don’t know how honestly the votes have been counted. But it’s clear that many Georgians voted for Georgian Dream.”

Why did they vote that way? Because they didn’t want a repeat of the conflict of 2008, when Russia invaded Georgia. “They thought that a pro-Russian party would allow them to live out the remaining years of Putin without another war.”

Meanwhile, Ukraine-watchers are responding to the news that 12,000 North Korean soldiers are joining the fray as a part of the strategic alliance between Russia and North Korea. This won’t make much difference, Khodorkovsky says. Since each Russian soldier costs Putin about $30,000, the influx of new troops “will save him maybe a few hundred million dollars, which is not a big deal in that context”.

More interesting, in Khodorkovsky’s eyes, is the question of how North Korea sources the ingredients for the vast supplies of munitions that it contributes to the Russian war effort: the copper, the cotton and the chemicals. “Do we know anything about any copper mines in North Korea?” he asks. “How about cotton or chemical production?” He clicks his four-colour ballpoint pen. Then he adds: “However, we do know that all of that exists in China. We know this very well.”

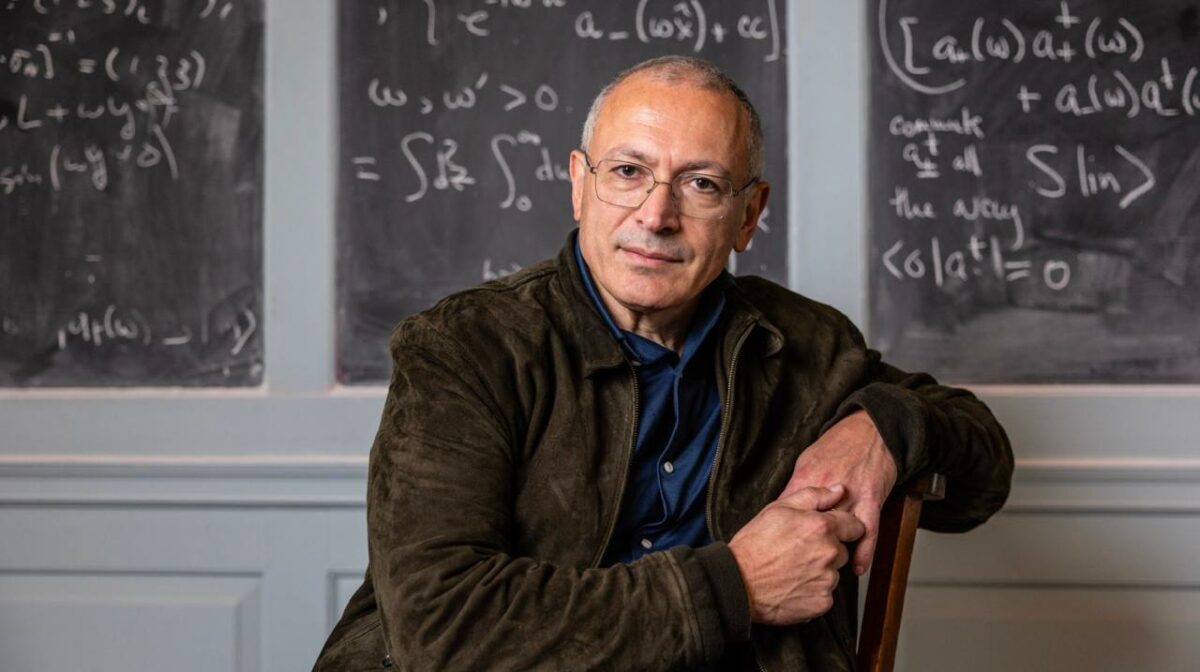

In person, Khodorkovsky is softly spoken, informally dressed, and unobtrusively handsome. We meet at his half-stuccoed London townhouse, where there is nothing particularly ostentatious about his lifestyle — the ground-floor room we talk in has a large bay window and a single oil painting. We drink coffee and mineral water. He has nothing. There is something almost monk-like in his mild manner, an air of patience accentuated by his tendency to do a gentle Indian head shake while speaking.

Why did he choose to make his life in London? Khodorkovsky’s first answer is that he moved here for the weather. It’s all relative: Moscow gets pretty cold. But this may be a joke, since he goes on to talk about his fondness for British irony. “I adore sarcasm.” He smiles. “The people around me do not adore my sarcasm. But this is something I love in Britain. People understand dark humour very well here.”

The knack for seeing the funny side served him well during the absurdities of the show trials he underwent after he was arrested in 2003 on charges of tax evasion and money laundering. At one point, he and his co-defendant, Platon Lebedev, asked their lawyers not to interrupt the monologues of the prosecuting counsel. “He was such an idiot, it amused us to listen to him.” They appreciated the performance like a comedy routine. “We just sat there, enjoying what he was saying.”

Another Kafkaesque moment came after the sentence. When the judge was criticised outside the courtroom, Khodorkovsky recalls wryly how the man’s press secretary leapt to his defence. “She actually responded, ‘Why are you attacking him? He didn’t write the sentence. It was given to him. He merely read it out.’”

Ten years of incarceration followed, during which, he has said, he underwent a transformation “from being a man who was far from ideal to being a man with ideals”. He now seems like one who has gained wisdom through suffering and learnt strength in the face of adversity. Was he supported during those dark times by any kind of spiritual faith? Does he believe in destiny, for instance, or God?

Khodorkovsky is silent for six seconds. Then he lets out a sigh that is almost a groan. Then he is silent for another 12 seconds. Finally, he replies.

“That’s a good question. I don’t know. For some reason I have a deep conviction that life does not end here. But I can’t tell you that I took this from the Bible. When there is a moment of crisis, and you realise life will soon end, at first it’s scary. But then for some reason I calm down.

“Because I have this conviction that, after the end, I should not feel ashamed of what I have done in this life.” He connects this internal morality with his belief in an afterlife. The idea that you must not feel ashamed of your life “only makes sense if there is life after death”.

It’s hard to imagine having this conversation with Putin, let alone Trump.

I was locked up like Evan Gershkovich. This is what the West must do

What most impresses about his book How to Slay a Dragon is that it doesn’t only focus on the lurid, albeit pressing, question of how to get rid of Putin. It also homes in on the deeper and more complex challenge of ensuring that one dragon isn’t simply replaced by another. By Khodorkovsky’s analysis, Russia’s systemic sickness is rooted in its staggering size — it’s nearly twice as big as China — combined with the fact that, for centuries, it has been ruled from a central power base in Moscow.

The result is that it’s impossible for a leader to control the country except by resorting to the gunpowder smoke and distorting mirrors of a dictator. “To hold power, they have to look for an external enemy. So for Putin, the war and the enemy is the way of seeking political control over the whole country. Because the only thing he can say to everyone from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok is: I will defend you.”

But go even further back in history and you find a Russia that was more like a federation. The Vikings called it Gardarika, meaning “country of cities”. This was Khodorkovsky’s working title for his book. The first part of his prescription, then, is the decentralisation of power — to create a modern Gardarika, with a collection of regional power bases centred on the variegated cities spread across the country.

The second part emphasises the need for an interim manager to oversee the transition from the centralised imperialism of today to a federalised future of parliamentary democracy, before walking away. “You should be able to do your work within a few years and then leave,” Khodorkovsky insists.

For all his immersion in politics, his foremost skill is management. “I’m a crisis manager of big systems. I can’t manage small enterprises. That’s not my thing. This is both good and bad. Because if there’s a crisis, I can help. If there’s no crisis, I fall asleep.”

One of the obstacles to achieving any of this, in evidence recently, has been the divisions within the opposition to Putin. Last year, in Berlin, Khodorkovsky organised a declaration denouncing Putin and the war in Ukraine, which was signed by 12,000 people. It was not, however, signed by members of the Anti-Corruption Foundation of Alexey Navalny. Since Navalny’s murder in a Siberian prison in February this year, divisions between the two camps have widened.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the man with a plan to topple Putin

This disunity, of course, is in the interests of the Kremlin. In about 2000, Khodorkovsky says, the Kremlin began giving money to the opposition party Yabloko. Why would they do that? It so happened that Khodorkovsky was friends with a Kremlin insider — Vladislav Surkov, now a strategic adviser to Putin — who told him the money came on one condition: Yabloko wasn’t allowed to unite with any other party. “This line is still being maintained by the Kremlin today.”

The implication is that the current dissent is being sown and nurtured. What’s needed instead is a coalition. Or as Khodorkovsky puts it, with his wry smile: “There are two types of sentiment in the Bible. There’s the one where they say, ‘Those who are not with us are against us.’ And there’s the one where they say, ‘Those who are not against us are with us.’ I’m in favour of the second type.”

The article was originally published in The Times