“I’m personally prepared to work with any political force that shares in these values.”

Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Evgeny Chichvarkin recently gave a press conference to talk about their working together. Below is an edited transcript of what they discussed, together with questions from the floor.

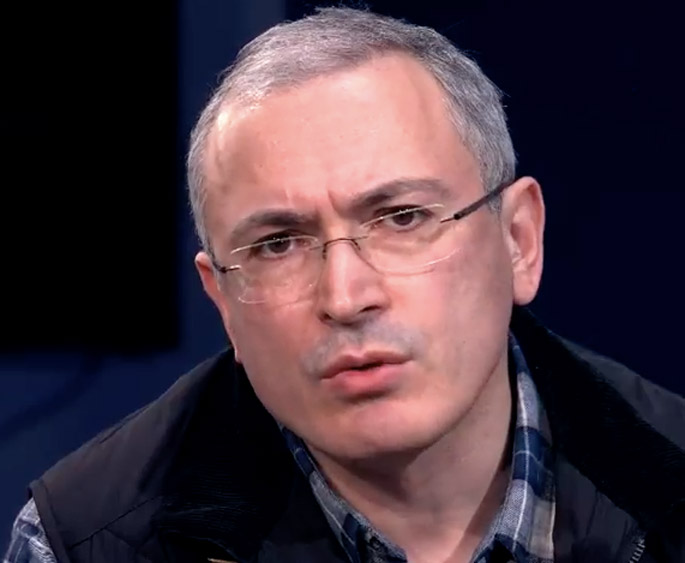

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

I’ve said many times that the departure of the current regime will not in itself entail a transition to a more just society. Although, of course, our current problems – corruption, the collapse of our economy, the collapse of our education and healthcare systems, all taking place against the backdrop of trillions in oil revenues – they’ve all been catalysed by the activities of this regime.

Nevertheless, when the regime departs the scene, a just society will not materialise of its own accord.

The main problems facing us now are down to a lack of trust. A lack of trust in the court system – we’ve no independent judiciary. A lack of trust in the majority of our media outlets – we’ve very few independent ones left, unfortunately. A lack of trust in our electoral commission – we don’t trust the way votes are counted. That’s what it all comes down to – a lack of confidence.

Beyond that, another problem is that we’ve a society with no aptitude for self-organisation, we’ve no proper political parties representing the whole of society, we’ve no country-wide, nationally renowned, independent, self-organised movements.

So when this regime departs the scene, even fair elections will initially be impossible to hold. We’ll need a transitional period in order to carry out political reform. We anticipate that this would take around two years. At this stage it’s possible and necessary to unite all political players who’re in favour of a regular turnover of power.

I’m talking about both right and left, statists and libertarians, supporters of multiculturalism and advocates of a national state. At this stage we can all work together. I’m personally prepared to work with any political force that shares in these values, that recognises the rule of law, that recognises fundamental human rights and freedoms.

I believe that all responsible political players should have the opportunity to convey their views to the public. And society should then be able to make informed choices.

What I’m involved in now isn’t a political project – or rather, it isn’t a party project in the fullest sense of the word. My only personal goal, as I see it, is to create an opportunity for Russian society to choose a course of development for itself via free and fair elections, and perhaps to err and subsequently to make new choices. That’d be mission accomplished for me.

To achieve this, you’d have to break the impasse on some key issues we face as a society. I’ve mentioned these already – we lack self-organisation, we’ve no confidence within our society,

we’ve no trust in our fellow citizens.

It’s these issues that I’m trying to tackle within the framework of our Open Russia projects. These projects are politico-educational in nature: their aims are to fashion a vision of the future, to facilitate education, to protect human rights, to provide society with independent information, and to help young politicians acquire political experience – that’s what we’re about.

I’m very pleased Evgeny’s joining us – he’s got significant management experience and he’s a recognised expert in the field of social communication.

Our views diverge on many issues. He’s a libertarian, I’m more of a statist. And when we hold our first fair elections – which, I hope, will happen within our lifetimes, but unfortunately not this year – Evgeny and I will most likely be voting for different candidates. But until that time comes, we’ll do our best to work together, and to work effectively.

Finally, I’d ask you not to confuse those first fair elections I’ve just mentioned with the quasi-elections we’ll witness later this year, and possibly in 2018 as well.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

On a personal note, I’d just like to say that I’d never planned to get involved with politics. I got my first taste of politics only when I was pressurised into selling my company by the siloviki [ruling elite]. Then I was very briefly involved with Right Cause. And, as you know, all liberal initiatives went down the pan. A few people are making some timid attempts to breathe new life into the movement, to rebrand it and what have you, but, to my great regret, I just don’t see any prospects in it.

Then for a while it seemed that freedom might waft our way from Ukraine, because Ukraine had witnessed a “Revolution of Dignity”, and it seemed that people were about to break the back of the imperial consciousness. It didn’t turn out that way.

Six months ago, a year ago, I thought Putin would be around forever. That’s that, I thought, our minds have been addled, there’s nothing to be done. But that’s absolutely not the case.

We’ve huge reserves of energy inside us – colossal potential. What’s this potential being squandered on? On fighting one another, on being aggressive.

Aggro at home, aggro on the roads. People are protecting their businesses, their homes, their property.

People’re squandering their vital energies on negativity: you know, “we’re surrounded by enemies” – the folks next door are enemies, the cops are enemies, the taxmen are enemies, the regime’s another enemy, and they’re trying to make enemies of the liberals. As for our neighbours… It turned out that our only friends are Abkhazia and South Ossetia, everyone else is an enemy. We’ve massive potential. We’ve massive intellectual potential, massive creative potential. We’re a hard-working nation, and a shrewd and enterprising one – in the good sense of the word. And we have to channel that into creating something.

Why are these two years so important? At some point after the revolution – if you can use that term to describe the fundamental shift in power that occurred after Yeltsin took office – freedom just dropped into our laps …

Perhaps no other country has ever paid such a small price for freedom.

The Soviet Union simply collapsed. At some point, the behemoth just rotted and fell. Then people had the great idea of banning the Communist Party, which was the right thing to do.

The Communist Party was banned and, for a long time after that, people – including current Kremlin personnel – worked hard to ensure that the monster wouldn’t rear its head again.

But on the other hand, the KGB wasn’t banned, the archives weren’t declassified. And what did we get? We got a horrendous reaction. And now we’ve had 15-16 years of what we might call negative selection.

For the most part, we’ve been moving backwards for sixteen years. The first four to six years, it was a case of one step forward, two steps back, but now we’re in absolute reverse.

The current regime has unequivocally stolen the future from us, stolen the idea of the future.

The paradigm of the regime leaves no room at all for young people, no room for the future, no room for any prospects.

We’ve a huge number of young people just dreaming of leaving. We just can’t let that happen! A critical mass of people has accumulated in London, for example, but they should be here [in Russia].

I don’t feel completely fulfilled. I’ve a perfectly functioning business [here in London] . [Back in Russia] I had 55 million customers – a third of the country’s population! Five thousand stores in nine countries. I know more or less what people’s problems are, from Baltiysk to Nakhodka, from Anadyr to Grozny.

Then there’s the Chechen problem. 90% of Chechnya’s population consists of grafters who live poorly and badly and who get robbed and cheated. And then you’ve got the handful of thugs who’ve been given wider-ranging powers by the current regime. But the bulk of the population consists of people who’ve got normal human problems.

If I can somehow be of use, if I can help somehow – that’s my dream, so to speak…

What will a Russia of the future look like? It’ll mean schools without guards. The phrase says it all. We have to learn, we have to carry out radical education reforms, drawing on the best elements of the Petrine era, perhaps even the best of the Soviet period.

We’re not building roads. That’s the direction the country’s leadership should be working towards. And that, I hope, is what we’ll be working towards over the course of that selfsame two years, when the regime drives itself into a dead end.

And it is driving itself into a dead end – and doing so by leaps and bounds. They’re making fatal mistakes, and making them with ever-increasing regularity. This is why we need to learn from the mistakes of 1991, and make sure it [the change of regime] happens as painlessly and bloodlessly as possible. “If not Putin, then who?” it might be asked. And I’d answer, “If not Putin, then the law.” Or justice, rather.

If not Putin, then justice. If not Putin, then an independent court system that allows you to defend your case.

We need iPhone-like laws.

What’s the beauty of the iPhone? The intuitiveness of it – you barely need to read the instructions.

The laws by which we live must be intuitive as well – we shouldn’t have to squander our energies on fighting the state.

We’ve no self-organisation. Now that’s something the Ukrainians do have, to give them credit. Their society is able to self-organise. We have it in us as well. We just need to release that potential. Unshackle ourselves, rid ourselves of our “crimestop” tendencies, and ultimately “take back our land.”

I’m very glad to have been invited to participate, and hope that all my remaining energies and intellectual capacities will be chandelled into a positive direction.

Questions and Answers

Victor Vasiliev (Voice of America)

This is a question primarily for Mikhail Khodorkovsky. It’s been reported today that the Federation Council isn’t excluding the possibility of branding Open Russia a “foreign agent.” Could you please pass some sort of comment on this news?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

I take a humorous attitude to the initiatives of our representative body, which would really do better to busy itself with the concrete problems facing Russia’s citizens instead of demonstrating that it doesn’t even understand its own laws.

For instance, how can the label of “foreign agent” be attached to an organisation which – first of all – isn’t foreign, and which, secondly, is funded by a Russian citizen? Furthermore, how can this organisation be dubbed undesirable in a country that proclaims itself democratic?

Evgeny Chichvarkin

What can we say about all this? The bear’s sated and hence isn’t hunting. In fact they’re afraid of us. So we’re sat here in far-off London, and they’re going to write, “What can those guys do? One’s stolen a load of oil, the other a load of phones.”

What’re you on about – in actual fact they’re terribly afraid! Because we’ve no restrictions, we say what we feel, we say what we think.

And what they fear most of all is that at some point people will prick up their ears.

Because what we’re offering and what we’re saying is ultimately predicated on normal humanitarian values.

Victor Vasiliev

In view of this information, and in view of the constant witch-hunts against organisations directly involved in elections, do you think it’ll be possible for this autumn’s elections to be conducted properly? And your attitude to the elections of 2018 – “quasi-elections,” as you called them – what’s your take on them in general? And when you announced today’s press-conference, you said that Putin has to go within some foreseeable time-frame. Could you be a bit more specific about that?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

As regards this year’s elections: they’re quasi-elections, as I’ve said, and they can and should be used as a politico-educational project. A project, that is, that will serve to showcase the new generation of young politicians to Russia’s citizens.

As for 2018, I’d love to tell you that I expect a change of regime by then. Speaking personally, I don’t think that’ll be the case. My own forecast remains the same:

we can expect serious change to have taken place in Russia by 2024,

or perhaps a few years prior to that.

Mikhail Sokolov, Radio Liberty

I have a question about the opinion piece by Investigative Committee chief Alexander Bastrykin. Are you familiar with this article, and what do you make of his strident proposals to restrict Internet freedom, to imprison people for incorrect interpretations of history, for any failure to recognise the [Crimean] referendum, and so on?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Well, Evgeny, this is your favourite topic.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

It’s clear that Bastrykin is a lackey of the regime, that, in fact, he’s under the direct control of Putin.

They can’t cultivate anything, they can’t construct anything, they can’t create anything.

To use the language of judo, they’ve got the country in a chokehold. That’s what they were taught, and that’s what they actually know how to do – they know how to maintain a chokehold. Whence all the latest restrictions.

Freedom of speech is a value that precludes mass casualties. Wherever there’s freedom of speech, there’s no mass starvation and no mass murders.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

We’d be happy to highlight a few issues Bastrykin ought to delve into, if he has the time for philosophical deliberations.

Vyacheslav Kozlov, RBC

I’ve a question about the current election campaign. It emerged recently that Open Russia-endorsed candidates, Democratic Coalition candidates, and candidates from Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation will effectively be standing for election in the same districts.

I’d like to ask whether this means that there can’t be any cooperation between Open Russia, the Democratic Coalition and Navalny? How did this situation come about and what’re you going to do next?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Cooperation is not only possible, it’s already happening now. And, as I’ve already said, I’m treating these elections as a politico-educational project which should give the maximum possible number of young political leaders the chance to present themselves and their views to the public.

This being the case, we should only be rounding each other out – by no means should we be competing amongst ourselves.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

And if you look at how Maria Baronova’s been reacting, she’s publicly stated on several occasions that the Navalny candidates are heading down roughly the same road and thinking along more or less the same lines as us, so there’s no divergence or incongruity here. It’s obvious that on the road to freedom we accidentally bumped shoulders, apologised, and carried on in the same direction.

Yury Timofeyev, Grani.ru

Do I understand correctly that this educational project – this opportunity for young leaders to gain political experience – is the only thing you’re going to do to facilitate Putin’s removal from power by 2022-2024? Is he going to depart the scene of his own accord, or is someone going to ask him to leave, and then you’ll enter the fray with your project? Or are you going to do something to facilitate Putin’s actual removal from power?

Evgeny Chichvarkin

If Putin is to be removed from power, educational initiatives are probably among the most important instruments at our disposal. Think back to how the Velvet Revolution began in 1989 – it began with student demonstrations.

Knowledge is a weapon in the twenty-first century,

and it was a weapon in the twentieth too. So it’s of critical importance that the “89%” gain access to a completely alternative vision of the world – an alternative vision of how a normal, human existence should be orchestrated in Russia.

As I’ve already said, it’s all about schools without guards – they should be able to see it, they should have access to it. The challenge facing Mikhail Borisovich and myself is to communicate this information, this knowledge.

And if we get accused of “inciting religious hatred,” or of failing to recognise the borders of the Russian Federation, or violating any other stupid new laws, we’re going to overcome these problems.

Because these laws – they’re not human, they’ve been improperly adopted by a parliament that wasn’t democratically elected.

So we have a goal of making our country strong and powerful – but instead of putting the frighteners on people with our tanks and Iskanders or flying fifteen metres away from American vessels, we need to be proud of the guy we put in space last year, and not just 60 years ago. But we’re only proud of our missions from 60 years ago.

So it’s all about knowledge and outreach work as well. Our problem as libertarians and liberals is that the notion of propaganda goes against the grain for us. Let’s call it “enhanced training,” say.

We’re going to champion and promote the ideas we believe to be correct. And if we violate any new made-up laws while we’re at it, well, okay, no big deal.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

And I’d also like to point out that our work with the politicians I mentioned earlier will extend beyond these elections or quasi-elections.

Our work will continue because opportunities for political self-presentation do exist in our country. In addition, young political leaders who prove that they can communicate with society will potentially be able to count on our support for their own socio-political projects. I hope this will create a trend indispensable for the removal of this irremovable regime.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

Temporarily irremovable.

Daria, Silver Rain Radio

I’ve a question for Mikhail: do I understand correctly that you’d consider a return to Russia, but only to a free Russia, and only following the holding of fair elections?

And secondly, with every passing year, Russia’s really falling behind – financially speaking as well … and yet, the repressions, the constantly falling incomes still aren’t activating the population. What, in your opinion, has to happen to activate people – is there some ceiling, some limit to people’s patience?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Thank you. Firstly, of course, I plan to go back at a point when the regime would face extremely negative consequences if I were to be incarcerated immediately.

That is, I’d be prepared to strike an additional blow at a juncture when that blow would be of decisive import. Today I know that my return to Russia would result in my being gagged following yet another spurious trial. I don’t need to tell you how these things happen. What could serve as the trigger or the “black-swan” event? It’s hard for me to say, although I sometimes give the example of a conversation I had with some Western political analysts who were feeling sorry for our Russian authorities: “here in France,” they said – I was speaking to some French colleagues – “if the government does something wrong, people start getting outraged, people take to the streets,” and we twig that we’re doing something wrong.

“But over in Russia,” they said, “everything’s different: people say nothing for ages, and then bam! the regime’s hanging from a branch. And that’s a problem.”

To my deep regret, these really are the laws our society lives by. People tough it out for ages and ages – and then immediately resort to radical action. I hope the new generation of leaders we’re helping to put on the political map will able to overhaul this practice.

We do need change, but it’d be good to achieve change without extreme measures.

Boris Pervushin, blogger

This question’s primarily for Mikhail Borisovich, but if there’s anything Evgeny can add, that’d be interesting to hear too. You were talking about a transition period. I’d be curious to know how you envisage that transition – would it be an electoral process, a revolution? Have you imposed any restrictions on yourselves in this regard, or are all means good? And how will we emerge from this transitional period? How should Russian voters respond to this pledge in light of the fact that you supposedly (or not supposedly) promised Putin that you wouldn’t get involved with politics?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

I anticipate that the transition period will be upon us whenever the public decides that it’s suffered enough.

Whether this happens today, tomorrow or in several years’ time depends in large part on the conduct of the current regime. Because any revolution is of course catalysed by whatever regime happens to be top of the pyramid at that given moment.

I’d prefer it if we didn’t parrot the myths that’ve been created by Kremlin propaganda.

I really didn’t want to get involved with politics, and would’ve stayed away were it not for what started happening in the wake of Sochi – the country veered abruptly in the direction of an aggressive isolationism, an aggressive consolidation of the current regime’s authoritarianism.

But I never promised not to get involved in politics, and I’d like to point out that Vladimir Putin directly acknowledged this fact on his Direct Line Q&A a couple of years ago.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

The objective isn’t to transfer power but to foster a proper political process,

to carry out the requisite reforms – judicial reform included – and to oversee the emergence of new political parties and the holding of elections. But whoever wins, wins.

Once those two years have elapsed and the transition period comes to an end, we’ll have an answer to the question of “If not Putin, then who?”

It’ll be whoever’s chosen by the people. Whoever has a proper political programme, a proper team, workable proposals. Whoever gains the country’s trust.

And our objective is to do everything in our power to ensure that whoever does win isn’t a Generalissimo but someone who will render service.

Going back to my former company, why did we become so popular? Because we provided the best service. Political power, too, must be contested by people who pledge to provide the best possible service – and prove that they can do so.

Generally speaking, the state’s function – much like that of the police, the army, or the waiter in the café – is to provide service. They’re not that different from each other. And the people who serve their country, their nation, shouldn’t forget that. Our task meanwhile, is to make sure that from now on, everyone will forever understand that the people they’re electing are being elected to render service.

Alexei Gorbachev, Nezavisimaya Gazeta

I have two short questions. At the beginning of your speech you brought up the unification of the opposition. An attempt to achieve just that has been made in Russia – I’m referring to the Democratic Coalition in particular.

I’d be interested to hear your take on Ilya Yashin’s suggestion that Kasyanov’s place at the top of the party list ought to be reconsidered. Secondly, it’d be good to get a fuller understanding of Evgeny Chichvarkin’s role in the set-up you’ve described. I get what his political views are, but is he going to play some sort of role in Open Russia itself – will he be deputy chair or what have you? What will he actually do?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

For now, Open Russia isn’t part of the Democratic Coalition. We’re allies, and I wouldn’t like to give my colleagues advice on such a sensitive issue, which, as far as I understand, has prompted serious debate within the coalition. Naturally, I’d like to see our colleagues and allies reach an agreement among themselves so their participation in the elections isn’t marred by internal conflicts.

For me personally, and for Open Russia as an organisation, cooperating with the Democratic Coalition doesn’t present any problems. We’ve always fulfilled whatever promises we’ve made each other, and I hope this’ll remain the case throughout the upcoming six months.

As for the role of Evgeny, I hope he’ll be able to describe that in more detail for you in a second. But I certainly hope his arrival at our organisation will improve the way we communicate with the public – this is something he does better than anyone else.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

Basically I’ll be working on the programme, on general branding and on the organisation’s positioning.

I’ll be doing everything in my power to communicate the ideas engendered here to every Russian citizen – and to communicate them as an alternative to the existing worldview, an alternative to what we hear being said on TV. They’re putting the frighteners on us, convincing us that there’s only one track, one tunnel to go down – whereas in actual fact there are many. We’re ready to join forces with people who, just like us, envisage a free Russia.

I think that when we had the opposition’s Coordinating Council a few years back, that was pretty much the very best thing to’ve happened to the opposition in recent times. Everyone was united by a common idea – everyone from Illarionov to Sobchak, from soft nationalists – yes, it’s unfortunate, but what can you do – to libertarians. That’s probably the right way to go about things, and something similar will probably emerge again.

The whole white-ribbon thing – which we discussed with the just-mentioned Yashin back in 2010 – that was effectively a rehearsal for a colour revolution.

We want to be part of the civilised world, and we’re faced with a difficult challenge: those who’d like to be part of the civilised world despite any differences of opinion, despite the fact that someone might be a blatant socialist… [sic] As Mikhail Borisovich had said, these are issues we’ll resolve later. But we have to unite against what is effectively a common enemy, to unite against the imperial (or even socialist-imperial) consciousness evinced by Putin and his team.

Generally, we mustn’t be afraid of colour revolutions. The Georgian revolution was absolutely bloodless, and its upshot, despite Saakashvili’s defeat 10 years later, has been that the country remains corruption-free in most domains. The first Maidan engendered the freedom of speech that made the second Maidan a possibility, and there’ll be a third change of regime in Ukraine because things just can’t go on like this. This is a political process we [in Russia] just can’t survive without any longer.

There was a question about how long people can tough it out. They can tough it out for any length of time, as demonstrated by the example of North Korea. Our challenge is to prevent Russia from going all the way down that road, because it’s obvious that animals are easiest to control.

Our challenge is to resist and to make sure we don’t sink to the level of North Korea.

Because the things the Putin administration’s currently coming out with are more or less tantamount to the ideas of the Juche.

Hochbar Ramazanov, Pulse UK newspaper

It’s a commonly known fact that a formidable military force – or at least an infantry force – is currently being built up in the Chechen Republic. What fate do you prophesy for Chechnya in the event of regime change, and do you think it’s sensible to keep pouring money into Chechnya with a view to maintaining peace in future?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Just like the other republics within the Russian Federation, Chechnya should of course have the right to self-determination. That is, if the Chechen people ever decide they want to secede from Russia, they should naturally have the right to do so.

But today, there’s no genuine opportunity for the Chechens to express their point of view – they’re effectively being held hostage by a medieval feudal lord, having been handed over to that lord by President Putin.

Why did he do this? I’m convinced that it wasn’t to put an end to the war. Or not only to put an end to the war, let us say. I’m convinced that he did it so he’d have an absolutely subordinate territory, politically speaking. A territory that helps him remain in power in return for money.

I know a lot of people from Chechnya and I’m convinced that, just like the rest of Russia’s citizens, they’re perfectly ready for a normal democratic society, to elect their own authorities, to live.

And I don’t think they’d want to secede from Russia – simply because I know these people. They’d want to educate their children in Russia, they understand that their children’s future lies within Russia’s borders. As regards the process of this transition and the dangers that exist today, I think that for the most part these are scare stories. Chechnya’s mostly home to absolutely normal people who want to live in peace, just like we all do.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

Can I add something to that? As I’ve already mentioned, my company had a branch in Chechnya, which we opened in 2004. We needed one of the few undamaged buildings [in Grozny], and that’s where we opened our first store.

Of course, we had stores in Dagestan and Ingushetia as well. I’ve visited Islam-dominated regions several times and I’d like to say that the majority of people there are real grinders and grafters who live paycheck to paycheck. We’re talking 90% of the population here – hard-working, unaggressive, honest people.

The example of Dubai demonstrates what Islam can look like, even if it’s still a non-secular Islam. There’s no political freedom to speak of in Dubai, but there is economic freedom. As our organisation’s libertarian, I’ll be doing my utmost to place a particular emphasis on individual freedom, economic freedom included.

There’s no doubt that eventually all the North Caucasus republics (and Transcaucasia as well, though that’s none of our business) will be perfectly capable of conducting their own economic affairs without getting massive handouts.

What’s seriously lacking is education. Sheikh Mohammed has recently appointed a new minister – a minister of happiness, tolerance and youth. She’s a 22-year-old straight-A student from the University of Dubai. This is exactly the road we need to go down if we’re to deal with the forces of bigotry that exist within every religion.

Just look at our Union of Orthodox Banner Bearers. Their worldview is horrific as well.

It’s clear that this is a problem and a serious quandary that needs to be addressed, but I’d like to say that for those two years that we’re planning to be an interim administration, Russia will be what Russia is on mainstream maps of the world.

After a proper political process has been set in motion, we’ll be able to talk about various forms of federalisation. Again, this is a question to be discussed with colleagues and experts. At any rate, though, all of our economic and political proposals will – in contrast to our Kremlin opponents – be presented on paper as step-by-step instructions detailing what we’re going to do when the “zero hour” arrives. That way, everyone will have familiarised themselves with it, and they’ll be prepared for everything, including tax rates, even.

Anna Kogan, Big Hearts Foundation

I do a lot of work with civil society, I have my own animal charity. I also keep bumping up against a lack of organisational nous and a lack of willingness on the part of our young people to change things.

Our young people have gone kind of passive, shall we say. You’ve already said that many want to leave. How do we explain it all to them? Now back in ’89, they wanted to change things, they couldn’t just hop on an EasyJet flight and take off. Now they say, “I want the country to be different. We took to the square and protested but nothing came of it. We need results now but we’re not getting any, there’s five, ten, fifteen years’ work to be done.” How do you convince yourself not to give up, what gives you hope that ultimately the people who’re going to catalyse this colour revolution will actually stay in the country, that they’re out there somewhere?

Evgeny Chichvarkin

They are out there, of course.

It was difficult to tell people that we’re not living the right way

when the average Russian was better off in early 2014 than at any other point in history.

It’s very difficult to tell them that something isn’t right, that we’re not heading in the right direction, when their fridges are full and they’ve just taken out a foreign-currency loan to pay for a shiny great-smelling new car.

It’s hard to explain to people that soon enough they’ll lose it all, including the chance to assert their rights, when things just keep rolling along.

But, now that the average Russian’s quality of life has seriously deteriorated as a result of macro-economic changes and sanctions, people have started asking questions for the first time.

And it’s clear that the majority aren’t prepared to blame themselves: “I didn’t listen back then and I was wrong.” While on TV they’re saying, “Those guys’re the enemies.”

This is the first or the second stage we have to go through. We’re a savvy nation – people’ll figure things out soon enough. You say that people took action in 1989. Now mentally open two fridges – one from 1989 and one from 2016. There’s your answer.

An empty fridge opens the door to the street.

Katya Nikitina, Russian Gap magazine

How far is it possible to understand what’s going on in Russia if you’re in London? What are your information sources? Conversations with friends, Facebook, the mass media? How do you maintain an understanding of the current situation?

Evgeny Chichvarkin

As Mikhail Borisovich has said, there are not so many independent media outlets. We can see them here and I subscribe to virtually all of them.

I have a fairly active social life and people also come and visit me; I keep in touch with anyone I can.

Unfortunately, I cannot go to Russia to speak at MGU or some corporation, then come quietly back to London. And if I go to Ukraine the problems will be more or less the same: total corruption, total absence of any kind of law, no honest law enforcement, so people are not equal in the eyes of the law etc. The problems are more or less the same. I have not assimilated – essentially, I continue to live my Russian life here: over the nearly eight years of living in emigration

I have not become less of a Russian [citizen] but more Russian.

I very much want to return and I should like to have a business, tourism – something creative which will produce a normal figure on a bank statement. I have had to engage in politics because that is the only way to take our country back [quote from Aquarium song The Train’s on Fire, sung by Boris Grebenshchikov, which became the rallying cry for glasnost]. The opposite has happened, but I promised myself I would stick to a positive agenda, so I shall stop there.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

During the course of my work in Yukos I was used to being in constant touch with 100-150 people and it is this number of people who have given me an idea of what is going on, and I mean constant communication. From time to time I had meetings with many more people, of course. After my release from prison I managed to reinstate my contacts and be in constant communication with the same amount of people – and 90% of these are people who are living in Russia. I am not short of information and there is no lack of understanding of the political processes and their underlying dynamics.

And, as I have already said, no one tries to hide the fact that over the last two years increasing numbers of civil servants, staff members of state companies, are looking to communicate with the opposition – and succeeding. So, as I already said, we shall be pleased to be in touch with anyone who thinks that not being able to vote a government out is not a good thing.

Alyona Vershina, Echo of Moscow radio station

Mikhail Borisovich, my colleagues would like you to comment on the fact that in Kiev at this moment the sentence on Aleksandr Yerofeyev is being pronounced. This is, of course, linked to the Nadyezhda Savchenko case. We should very much like to know what you think about this. Will there be an exchange? And, generally, the behaviour of the Russian government.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

I have two views on this subject. Firstly, I think that one should not betray one’s own people and what the Russian government has done amounts to betrayal. Secondly, if we want to turn over the page of armed hostilities, then, of course, we need a full prisoner exchange or the story will never end.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

I have almost nothing to add to that: we should have an immediate and total exchange of prisoners. The more the Russian media says that there are two soldiers in Ukraine, the more likely is it that our government will not be able to wriggle out of the situation and we have to use our good offices to see that they are returned. For that to happen, we shall have to hand over Savchenko, Kolchenko, Sentsov and others.

Yes, a full exchange – our positions are exactly the same on this. There are the Minsk agreements and these are essentially all prisoners of war, so they have to be exchanged and soon.

Oleg Bogomolov, National News Service

I have a question for Evgeny Aleksandrovich. Our sources tell us that before Open Russia you were considering joining United Russia. Could you comment on that?

Evgeny Chichvarkin

Since about 2004 I had been receiving very pressing invitations and in 2006 there was low-key blackmail – well, perhaps you can’t quite call it blackmail, but an insistent demand that I join United Russia. To give it its due, it did at the time look rather more appealing than it does today.

The only moment of coordination was when the topic of what Russia would look like in 2020 was being discussed – there was an elite round table and I was invited as an independent presenter, without the need to join the party. I was pleased to accept, it was interesting and I have no regrets on that score but I don’t think I shall be invited back.

There’s a marvellous photograph of me in a yellow t-shirt standing with Luzhkov and Vorobyov – have a look. It was interesting and I never came as close to United Russia as I did at that moment. Then I was a member of Right Cause and tried to help with branding. My suggestions were not accepted and I am now trying to do the same thing at Open Russia.

Mariya Lokotetskaya, Business FM radio

As someone who has covered all Mikhail Borisovich Khodorkovsky’s trials, I have to ask what is happening with your third case in which you have been accused in absentia of the murder of the Nefteyugansk mayor Vladimir Petukhov. How much do you know and are you intending to hire lawyers, or is it all a matter of complete indifference to you?

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Naturally one cannot remain indifferent to such charges. But you have been an observer on the outside, whereas I have observed from the inside and we both understand very well that it is impossible to defend one’s good name in what currently passes for a court in Russia. For this reason, I shall of course not take part in any kind of trial, so what Markin and Bastrykin think up is of no particular interest to me.

Evgeny Chichvarkin

They do as they’re told.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Absolutely.

Sergei Gorashko, Kommersant newspaper

Mikhail Borisovich, I should like to hear what you have to say about supporting the Open Elections candidates.

There is a defined list of candidates whom the project has agreed to support, which means that they have access to some kind of resources, specialist advice. What about financial support for these candidates? Is there any, how is it done and what kind of money are we talking about? How is it going to be done in such a way that the money is not foreign? We know that State Duma election candidates cannot be financed by foreign money: it’s not allowed and they would simply not be registered.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky

Thank you very much. I spend all my time trying to find out from honourable people at what moment, for example, my money became foreign. I am a citizen of Russia, though I may at the moment be living abroad, but I am not a citizen of another country and, fortunately, the Russian Federation does not ban me from taking part in both the elections – which I am trying to do – and the election campaigns of others.

Recently, however, more and more limitations are being dreamed up. Nevertheless, they haven’t yet gone as far as banning Russian citizens from taking part in election campaigns.

I expect that the candidates on our list will be able to find support among their followers, Russian citizens, outside the specialist, organisational and other kinds of assistance we are offering them. Because if they can’t, that means we have selected the wrong people. So I don’t see that there should be a problem. Naturally I hope they will not accept any foreign funding.