Mikhail Khodorkovsky: “It Is Hard to Imagine the Possibility of Release: Ten Years in Jail is No Laughing Matter”

Before his 50th birthday, Mikhail Khodorkovsky was interviewed by Yevgenia Albats for The New Times magazine, which has published the interview in three parts. The first part is translated below and can be read in Russian HERE.

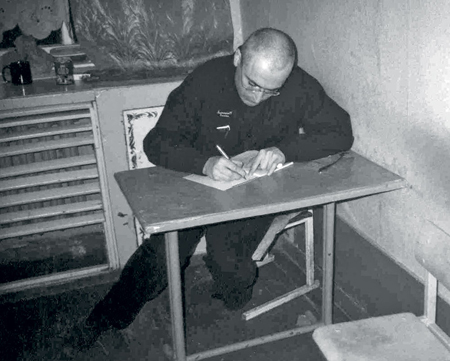

On June 26, Mikhail Khodorkovsky — once the richest person in Russia, now one of Russia’s most famous prisoners — turns 50. He has spent nearly ten of these years in jail. During that time he has lost the YUKOS company he created, and his wealth, while his children are growing up and his parents ailing without him. The power thought Khodorkovsky would be forgotten — the way many had been forgotten, especially those who were successful — who had not been hugely concerned about their reputation at the time when profit margins were the focal point. Khodorkovsky has been through humiliation, jeers, antagonism, and condemnation: “It serves him right”, some suggested. But he survived. He thought. He wrote. He did a lot of rethinking. And public opinion turned around. MBK, as he is ubiquitously known, became a moral authority for many. And not just because prison colony inmates are traditionally pitied in Russia — he proved that he could not be brought to his knees. His choice — either standing tall, or in a burial shroud. From the camp, IK-7, in Segezha (Karelia), Mikhail Khodorkovsky answered The New Times’ questions.

50 years — an age when people “roll the film back”, look back on the past, and say: if it were possible to turn the clock back 25 years, I would have acted differently – I would have taken a different decision here, I would not have made those stupid mistakes there. But history, like our individual pasts, does not have a subjunctive mood, and we cannot change the past. But one can analyse it. And so, if you were to draw a line on a piece of paper and divide it in half — on one side “I was right”, on the other “I was wrong” — what would be in each column?

At 50 years one can indeed take stock of some things, and in my conditions, really should. There is a risk that there won’t be enough time to finish the exercise. Indeed, this is just what I did in my book.

The most important points would be:

– I’ve got a fantastic family – four children, a granddaughter, parents, a wife I’ve been in love with for a quarter century already – an enormous plus;

– I have given them little time — a minus;

– my first marriage, when we were still in college, didn’t work out — a minus;

– but we have maintained a good relationship — a plus.

Of the rest:

– I headed a large enterprise and achieved good results (it’s amusing to recall that V. Putin once used those words in a congratulatory note to me) — a plus;

– I have spent ten years in jail because I strove to increase the volume of production (that’s what it says in the verdict!) — a minus;

– I was the first in Russia to create a programme to train schoolteachers en masse to use the internet (the Federation of Internet Education); you will be surprised to know that it too received a presidential prize in the field of education — a plus;

– it received this prize when I was already in jail — a minus…

There is a lot — things that I am proud of and things I am ashamed of. Views change with time: important things stop being important, and vice versa… The main thing is that my life was not empty. I have things to remember.

How old do you feel yourself?

I can’t believe that I’m 50 already! 40 at most! Alas, health professionals do not share my optimism.

How are you intending — if you are intending at all — to observe your birthday in the camp?

I hope I’ll be able to treat my colleagues in misfortune with tea and candies, and on June 27 I’ll receive a visit from my wife and children. The last time we saw each other was in March.

Fate

Imagine, if you will, that you are once again on that airplane, flying to Novosibirsk where they arrested you*. Imagine if you will, that sitting in that airplane, you find out exactly what is going to happen to you in the next ten years — two trials, terms, jails, camps, your boys growing up without you. How would you have directed your fate? (*Armed FSB commandos stormed Khodorkovsky’s charter plane in Novosibirsk’s Tolmachevo airport on 25 October 2003).

Back then? I’m afraid I would have shot myself. My current experience would have been a shock for the me I was back then.

These last ten years, from the people you knew from your pre-jail surroundings, what have you experienced more – betrayal or, on the contrary, loyalty?

I confess, I had thought less of people than is actually the case. Some of them showed themselves in only a slightly better light, while others, like Vasily Alexanyan — reached unattainable heights. Some I didn’t know nearly well enough to get an impression, but they turned out to be real human beings, like Alexey Pichugin.

You have written a whole series of articles over these years. One — “Left Turn” — surprised many people at the time*. Do you think now as well that the leftist idea is going to dominate on the Russian political stage in the next few years? In general, what kind of ideology — nationalistic, liberal, leftist, fascist — can carry the day in the next few years? (* Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s article “Left Turn” was published in the Vedomosti newspaper on 1 August 2005).

At that time I was predicting a “turn to the left” as a universal, and not only Russian, trend. It has happened. The paternalistic call hasn’t gone anywhere today, but it is gradually being transformed into a call for honest rules of the game for all. From here it is only a small step to people becoming aware of themselves as citizens and to the building of a national democratic state. This component part of the ideology will soon become the dominant one; other shadings — leftists/rightists, conservatives/modernisers and the like — will occupy their niches. I don’t think that it’s possible to skip over this stage of building a civil nation and to save the country.

A lot is written in the West about how Russians — thanks to having had a non-liberal history and political culture, being accustomed to a strong hand, being unable to organise themselves, and so on — are not predisposed to democracy. But what do you think — after all, camps and jails have allowed you to see the widest variety of people, including also, as they say, the salt of the earth?

Yes, today in our society there is a great dearth of mutual trust and ability to self-organise. But it hasn’t always been like that, and this experience has been preserved. What is necessary for its awakening is to move the centre of gravity of the state administration over to the municipal authorities, and returning to them the necessary sources of resources and powers.

The value of freedom — how is it perceived, and is it perceived, by people in jail?

The biggest proportion of inmates aspire to walk out of the prison gates even “into nowhere”, without housing, work, or family. Only a small number would be prepared to voluntarily return to the warm “security” of un-freedom. By the way, after five to ten years, many break and are no longer afraid of freedom.

Jail

What kind of people are sitting in the camps? There is a certain idealisation of camp inmates in Russia. What is the reality?

In the main, people are there for burglaries, robberies (stealing telephones), and narcotics. There are much fewer of everybody else. There are a great many false imprisonments with respect to cases of narcotics and rapes. With respect to narcotics, they lock up “users” who have refused to give up their dealers, falsely charging them with dealing. Charges of rape have become a business for prostitutes and the individuals who provide them protection. The overwhelming majority of the prison population consists of absolutely normal people, in a sober state. The drunks and the junkies are a catastrophe. There are approximately as many total sociopaths “with ice in their veins” and “professionals” here as there are completely innocent people: 10–15%. There are many who have had something else pinned on them on top of the crime they actually committed; the authorities do this in order to “close the case” and make the statistics look good, and in so doing they effectively cover up for the real criminal.

Ten years in jail — how can one endure this? The trial in the “Bolotnaya case” is only just starting up now. It is already clear that many will go by stages [a poetic way of saying “will be transported (‘staged’) to far-off prison camps”—Ed]. How can young and not so young people — yesterday’s students, computer company employees, businessmen, journalists, or scientists — prepare for this? And can one prepare for jail? What advice would you give them, based on your own experience? How to build relations with common criminals? And how with the camp authorities? What should be avoided? For example, you write in your book* that one must not allow so-and-so to be put into a separate cell or in solitary confinement in the event of threats coming from ordinary criminals. Why not? (* Mikhail Khodorkovsky, Natalia Gevorkyan, Prison and Freedom, Moscow, 2012)

You should not be afraid of jail; the absolute majority here lives “normally” — without hunger and beatings.

It is important to position yourself properly and to maintain your style of behavior. “Properly” means in the way that is acceptable to the person. The latitude is sufficiently large: from working for the administration to inflexible opposition to it — in human-rights mode or in the mode of “disavowal” (the “thieves’” mode). The majority chooses a middle ground of behavior — they “dissolve in the lineup”. It’s easier that way. The existence of support on the outside has huge significance. If a person has relations and a lawyer visiting him, they try not to mess with him unnecessarily: nobody needs scandals.

It is a big mistake to try and get some kind of local “privileges” while at the same time demanding everything that you’re “due”. You’ll pay for something like that. But you do need to know the laws.

Cells and “safe areas” — these are a big risk. Anything at all can happen to a person there. To be among the masses is the best protection.

There are no secrets in jail. It is customary to share. Excessive kindness or generosity are perceived of as weakness and are fraught with consequences. Politeness and carefulness in your choice of words are welcomed. Imposing your own rules of behavior is a heavy and dangerous task. It is better not to attempt this if you don’t really need to.

Ongoing amicable association (“doing the family thing”) in a group of three to five people for everyday housekeeping matters is useful, but the choice of “family members” requires great caution. You need to understand that this is not friendship, but collaboration. There are no friends in jail; beware of people trying to be your “friend”.

The camp, as I understand it, is built on understandings [prison slang for “unwritten rules”—Ed.] What are these understandings? How much do they differ from those that exist on the outside? What understandings have you accepted? Which ones were the hardest for you?

There are far fewer of the old “understandings” nowadays. Especially among the first-timers. Those who graduated from the juvenile colonies do attempt to impose one thing or another, but the adults laugh at this. Money, connections — they play the same kind of role in the criminal world as they do in our ordinary world.

The only thing that’s still left is maintaining distance from the “informals”. You can end up in their number both for not maintaining distance and simply because of needlessly excessive openness in telling about your family relations. The rest, including the confrontation between “reds” and “blacks”, is based not on understandings, but on an ordinary precept: don’t do unto others as you would not have them do unto you.

Unfortunately, a rule — an “understanding” — that I liked is gradually getting blurred — you have to be accountable for the words you’ve said, the obscenities you’ve uttered, the promises you’ve made, and the obligations you’ve taken on. As they say here: people don’t ”watch their tongue” any more, and they’re less and less accountable for it. The same as on the outside, by the way.

What was the hardest thing of all for you to get used to in the camp? And what things in the camp system have you categorically refused to accept?

The heaviest thing of all for me is to be without kindred people, without family. Some people are infuriated by the harsh routine, some by the local “cuisine”, some by the clothing. None of this gets to me personally at all; the only thing that unnerves me is the mutual lying and the universal distrust. I don’t accept this. I try not to lie myself and I try to trust people. With my character, this works more often than not.

You write a lot in your series “Prison’s People” about the unfairness of the judicial system in Russia. After ten years of being acquainted with hundreds, if not thousands, of those who have ended up in the camps, how do our courts look from that side of the barbed wire? What kind of principles does our judicial system have? What objectives?

I am convinced that we do not have a judicial system as an independent branch of power — which is what it is supposed to be according to the Constitution. It has been transformed into a chunk of the vertical of executive power, in its carrying out the functions of handling disputes between citizens and setting punishments.

The executive power demands that the courts adopt concrete decisions sufficiently rarely — when this touches upon its interests. Unfortunately, these rare but loud instances pervert and warp the entire system.

There is a self-censorship in effect at the level of court chairmen and the judges themselves whereby they do not allow themselves to overstep the government’s unspoken, constitutionally unlawful rules. Those who won’t “play ball” are punished without fail, although experienced chairmen simply don’t give potential troublemakers controversial cases.

On the whole, the system is oriented towards drawing up documents and setting punishments, without casting doubt on the conclusions of the investigator or the police (if is the case is criminal or administrative). And of course, if there aren’t any “special instructions”.

The courts, as I have already written once, are today no more than a cog in the “law enforcement” conveyor belt. That is how they perceive themselves.

You write that 10–15% of those who are sitting in camps and jails are victims of Russian justice. What groups of people turn out to be in these percentages? Under what kinds of cases? What should they have done at liberty in order to protect themselves from the arbitrariness? And is this possible in principle?

Besides the main groups about which I wrote earlier (pseudo-narcotics dealers, pseudo-robbers and pseudo-rapists), among the innocent are victims of various campaigns: pseudo-bribe-takers, pseudo-pedophiles, and, of course, our law-enforcement system’s favorite “fodder” — pseudo-fraudsters. There aren’t many of them, but it is specifically on them that the system makes its main money. Here we’ve got everything from unlawful raids, to participation on the favourable side of an ordinary civil dispute, to helping banks “collect” unpaid debts, to much else besides (including politics).

I think that here lies the main reason for the proposed amnesty not taking place — it would have deprived the regime of a major prop – a major source of its customary perks , for one year (since aside from anything else time would be needed to accumulate new “material” [a new revenue stream – Ed]).

By the way, there are real fraudsters too, and, mainly, a great many corruption cases, where our law enforcers, not wanting to “dig upwards”, have substituted the Criminal Code article “fraud” for the article “bribe”. In that way, you don’t need to “expose” the final recipient, having stopped at the middleman.

In order to protect yourself from undeserved jail, you need to either have a dependable “roof” [“protection” or a highly-placed “patron”—Ed.], or not be in Russia. The second one is the most dependable of all.

What habits have you acquired over these ten years of jails and camps that you didn’t have before?

I wake up if someone is looking at me. This is a result of the nighttime stabbing with the knife*. I don’t keep papers, letters, or photographs — otherwise the searches take forever, while the letters of people who are dear to me and my notes are subjected to meticulous scrutiny. At breakfast I eat bread with porridge. There’s probably a lot more that I don’t notice about myself. (* The stabbing against Mikhail Khodorkovsky took place during his first term, in the colony in Krasnokamensk on the night of 13–14 April 2006: one of the inmates slashed Khodorkovsky’s face with a cobbler’s knife while he slept)

What is the most intolerable thing in jail for you? What was experienced especially acutely at the beginning of the term? What later? What is continually intolerable?

At first, the most intolerable thing was to read and hear how they’re calling you a fraudster, how they’re tearing down YUKOS, and how they’re going after people; it was painful to watch the distress of my family members.

Later, the charges stopped inducing rage, but rather laughter, and they destroyed the company, but as for the people and family… I’d like to be able to abstract myself, but I just can’t.

In one of the interviews you said that in the fourth year you get used to non-freedom. What does “getting used to non-freedom” mean? And what is it impossible to get used to?

Being used to non-freedom — this is not being distressed by the impossibility of being alone, of strolling in the forest or along the streets of the city; not being distressed by the obligation to carry out the wildest demands (along the lines of lining up in formation in order to enter the barrack); and not being distressed by the understanding that all your personal things are going to be regularly searched, letters and photographs looked at and so forth.

Food, clothing, quantity of books, work — everything is regimented, but with a sufficient level of self-discipline it is not hard to get used to this. Although many literally lose their minds. The only thing I haven’t been able to get used to is being separated from my family.

The three main myths that jail has demolished?

1) That we’ve got a judiciary, 2) that innocent people don’t sign confessions, 3) that “the police” and criminals are not alike.

What do you dream most often in jail?

I don’t remember my dreams.

What do you think about when you’re feeling bad? Does it happen that you read poems? If yes, then which ones?

When I’m feeling bad, I don’t read, I write. Then I tear it up. As for poems, I rarely like them, inasmuch as I’m used to speed-reading and I lose their rhythm. But now Guberman and Vysotsky — I like them. The rest — one or two works each by various poets, from Pushkin to Galich and Okudzhava.

In jail you are — by virtue of your position on the outside, and the significance of your name, and your term — an authority. For what kinds of advice do people come to you most often? How do you set people at ease?

In jail, as on the outside, I’m more of a symbol. That’s what they say. And they rarely ask questions. In the main they ask me to comment on something they saw on television. Although conversations “about life in general” do take place on rare occasions. There are few people here with my life and jail experience.

Your most powerful human discovery in jail?

Probably nothing has impressed me as powerfully as people’s internal decency and courage – their readiness to suffer adversity in order to remain true to their own conscience. I thought that these were unique distinctions of but a few, but it has turned out to be the opposite – there are only a few completely without conscience, not even enough for all the positions in the bureaucracy. And indeed people sometimes even choose death. Why? Upbringing? But where did they get upbringing from? Their families are different, their surroundings are different, their state ideology is different, but the basic ethical norms of the majority are the same, even if we don’t adhere to them. You could put together several chains of logic but the question remains “why is it like this, and not some other way”. For me, the answer became Faith.

Your loved ones come to you: parents, wife, and children. Regard what questions is it hardest of all for you to find a common language with them?

It’s hard with the younger children — after all, they were very small when I was arrested, and now they’re teenagers.

What things from your previous life do you yearn for most of all?

The concept of “yearning for things” is not applicable for me. You can only yearn for living creatures: people, sometimes animals. As for things, I’ve got a pragmatic attitude towards them: the lack of a computer and the inaccessibility of a normal library (network-based and even an ordinary paper one) hinders me.

When a person is torn away from everybody and everything for ten years, do they develop a fear in the face of the outside world, beyond the barbed wire?

I’ve got it easier than many — people who love me are waiting for me.