No can do in Doha

No can do in Doha

For Russia, the collapse of the talks with OPEC in Doha is nothing short of a disaster.

Yesterday, in Doha, half of the world’s oil producers failed to reach agreement on a production limit, with predictable results when the markets opened today – all of those names and acronyms falling in unison, names that many of us perhaps couldn’t accurately identify with any certainty: Brent, LCOc1, WTI, FTSE … Although our lives depend on them.

Nobody can predict what will happen now – even the delegates in Doha were taken by surprise at their failure to agree – but it’s safe to say that the oil business will be even more of a free for all, with everybody fighting for market share, driving down the price ever lower, until finally it finds a floor, at $35, $30, $20 … Everybody who sells it is hurting, and even those who buy it don’t seem to be seeing much of a fillip in consumer spending and investment.

For Russia, the collapse of the talks with OPEC in Doha is nothing short of a disaster. Going into the meeting, the Kremlin had put considerable effort in to talking up the possibility of a deal, none more so than Energy Minister Alexander Novak. But others were not so confident. Mikhail Krutikhin, from RusEnergy, says “this meeting was doomed to failure from the very beginning. A few countries get together and say, ‘Let’s reduce our market presence and withhold some of our oil – our revenues will go down and we’ll cede this market niche to the States and Iran.’ There’s absolutely no logic in that.

“Production hasn’t been frozen in Russia – on the contrary, it’s rising, as we can see. Noises were made [about implementing a freeze]. But you’ve got to consider who the noises were made by – namely the energy minister, the representative of a completely impotent department that wields absolutely no power in the energy industry. They’ve got no mechanisms they could use to regulate yield, consumption and export volumes. They’re just a statistics office, and they get totally misleading information from oil companies, which they then use to draw up energy strategies that don’t make a blind bit of difference to anyone.”

And Krutikhin was brutal in his assessment of what will happen next.

“I think that the market will now react in the most straightforward fashion: oil prices will plummet again before bottoming out anew. Rock bottom will be in the region of $26-27 per barrel. We’ll then see oil rebound to the middling price of $45 a barrel we predicted back in late 2014. This may prove highly unpleasant for Russia.

“Now, if oil remains at $35 per barrel until the end of the year, they’ll have to print an additional 5 trillion roubles, which would be extremely bad news. Furthermore, we may well have exhausted our Reserve Fund before the year is out, forcing us to dip into the National Wealth Fund – a highly unpleasant scenario for the Russian economy.

“Cheap oil in Russia is coming to an end. Even according to official data, ‘hard-to-recover’ oil comprises 70% of our total reserves. Who’s going to work with these reserves when production costs are $50-70 per barrel? You produce oil at $80 a barrel and sell it on for $35. What kind of business is that?”

Russia needed a deal in Doha as much as anybody there, because, after 16 years in power, the Putin government is not only still dependent on the price of a barrel of oil for its survival, but is facing elections to the State Duma in September. With an economy in recession, a tight budget, and now no hope of rescue from a rebound in oil prices, for the first time, the Kremlin has very little scope for its usual pre-election manouevres – repairing the roads, doling out money left, right and centre. The election result, unfortunately, is still a foregone conclusion, but how that result is achieved will not be pretty, because with a restive populace (no matter the president’s high approval ratings), the government will not leave anything to chance. So, at home, we are looking at increasing repression and voting shenanigans, and abroad, more of the same strident anti-Western rhetoric.

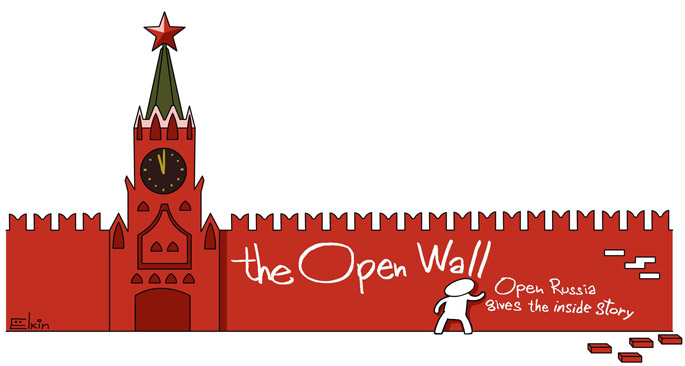

Or perhaps not. What was noticeable about the president’s stage-managed Direct Line, talking with his subjects last week, was the conciliatory tone he struck when talking about the West, suggesting that perhaps he knows how much of a corner he is in. How the West responds to that olive branch is what we are about today, because something else happened this morning, which shows that there is an alternative to an oil-dependent Russia, imagining enemies everywhere.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Evgeny Chichvarkin – the mercurial mobile phone magnate whose business was also taken away from him – held a simultaneous press conference in Moscow and London, to talk about their vision of an alternative Russia.

“Our aim is to engineer the removal of Putin and his friends, from government relatively soon, to launch the political process in Russia and to organise the first absolutely free and fair elections. Creating the necessary conditions for these elections will take two years from the moment the present government stands down. During the two years of transition we shall introduce a series of reforms, including political reform to establish the system whereby the government can be voted out in an election, judicial reform, which will lay the foundation for an independent judiciary in Russia, and a raft of economic reforms.”

I will leave you to ponder on that vision, ask yourself if you wouldn’t prefer to live under, work with, such an open Russian government; and we’ll talk about it in more detail later this week.