No substitute for success

The Kremlin says that import substitution is rebooting the economy, but that’s not what the figures say.

Georgy Neyaskin

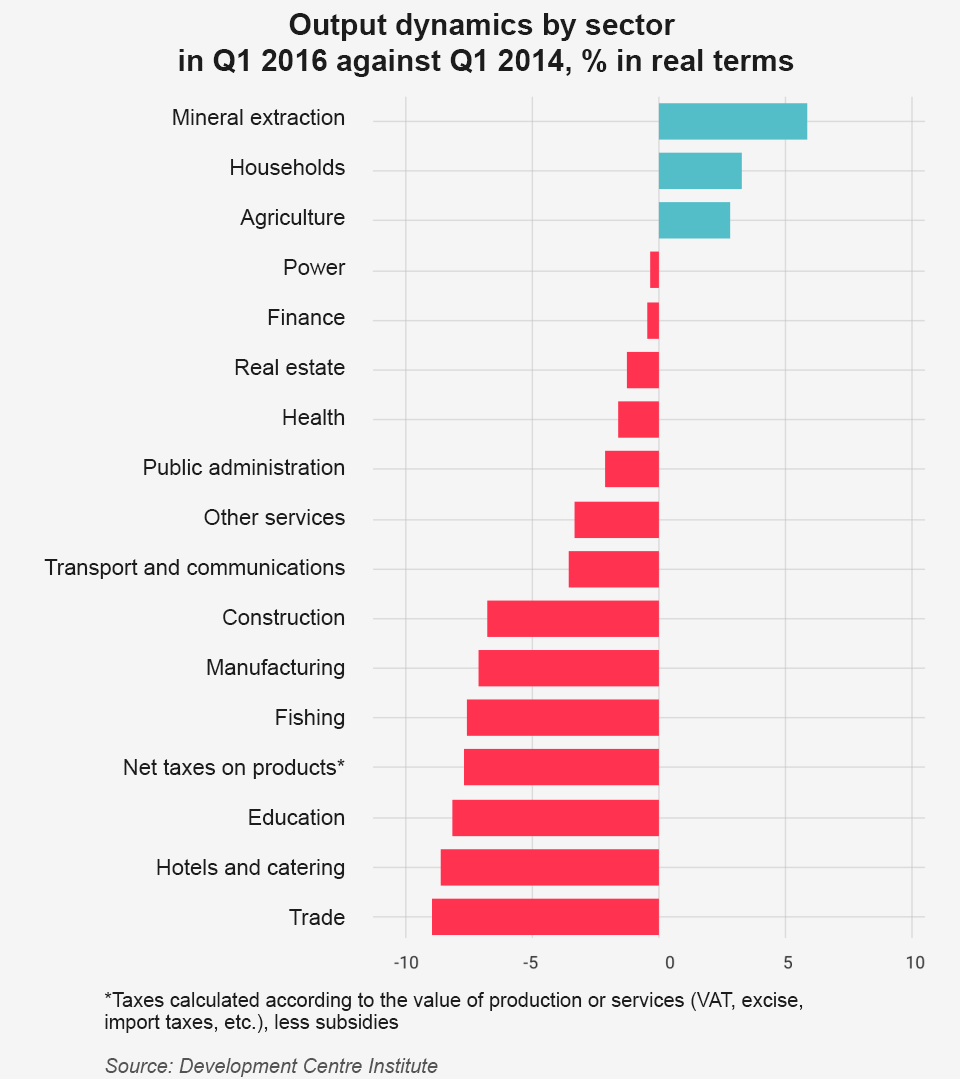

2014 was not only a year of gloomy forecasts for the Russian economy (the worst did not materialise), but one of tentative hope that the country would finally begin to wean itself off its resource addiction, and the weak rouble would stimulate import substitution across a range of sectors. The facts, however, suggest that the commodity sector weathered the storm best of all, while most other industries sagged.

In the first quarter of 2014, only three sectors saw growth: mineral extraction, small businesses (unincorporated family businesses, individual entrepreneurs, etc.) and agriculture, the latter aided by counter-sanctions on food. Worst affected were those industries directly dependent on consumer demand: wholesale/retail trade, hotels and catering.

“The weak dynamics of the manufacturing sector, which once again showed negative growth in 2016, is causing the de-industrialisation of Russia’s recession-hit economy,” writes economist Valery Mironov in a report for the Development Centre Institute of the Higher School of Economics.

It suggests that the Russian economy is moving away from developing new diverse industries backed by strong domestic demand and investment. The trend can be bucked, but only if Russia can shift towards producing goods for import substitution and export (other than raw materials), notes Mironov. The services sector, which burned bright during the oil-fuelled years, is unlikely to make a full recovery, he cautions.

Growth is being hindered by the hazy future facing the country, which is stifling economic activity. What’s more, since the start of this year the rouble has strengthened, making local products less competitive on the world market, writes Mironov. As he sees it, the Kremlin’s current policy of lurching from one extreme (unregulated market) to another (Gosplan-style state planning) is only adding to the uncertainty.

“It wouldn’t be a bad idea to find some middle ground,” says Mironov.

This article first appeared in Slon