Pavel Khodorkovsky: “Putin has got two perfectly concrete objectives”

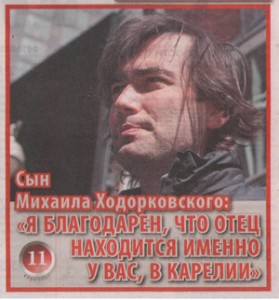

Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s son, Pavel, has given an interview to Karelia’s newspaper, Karel’skaya Guberniya, the translated piece can be found below.

Pavel, son of the famous “Karelian jailbird” Mikhail Khodorkovsky, chatted with Karel’skaya Guberniya via Skype. He has been living beyond the border for a long time already, and has not shown up in Russia since his father’s arrest (the former head of YUKOS was detained on the morning of 25 October 2003 on board an airplane at Novosibirsk’s “Tolmachevo” airport). If you have a webcam, Skype allows you not only to converse over the internet, but to see the person you’re talking with as well, so it did not escape our notice: the smiling 27 year old lad was sitting in front of a multitude of formulas.

Pavel, son of the famous “Karelian jailbird” Mikhail Khodorkovsky, chatted with Karel’skaya Guberniya via Skype. He has been living beyond the border for a long time already, and has not shown up in Russia since his father’s arrest (the former head of YUKOS was detained on the morning of 25 October 2003 on board an airplane at Novosibirsk’s “Tolmachevo” airport). If you have a webcam, Skype allows you not only to converse over the internet, but to see the person you’re talking with as well, so it did not escape our notice: the smiling 27 year old lad was sitting in front of a multitude of formulas.

– Pavel, what kinds of things are you doing in New York?

– I’ve got two professions. First, I’m a technologist, I’ve founded a company that produces electric meters that get connected to the internet and show how electricity is being used at the level of individual electric furnaces in commercial buildings. In fact, I’m in my office right now. Second, several years ago I founded the non-commercial organization “Institute of Modern Russia”. Its objective – the advancement of democracy in Russia.

– An interesting choice. You didn’t want to follow in your father’s footsteps?

– Actually, I very much wanted to. But my hopes were rather cruelly dashed. This probably happened around grade 11, when I started looking at universities and thinking about what country I’d go to to continue my studies. My father and I had a talk, and he explained to me that he didn’t have any plans for passing on the business by inheritance within the family.

– Why not?

– Well, you’ve got to know my father to understand this. When choosing people to manage his organizations, he’s always been guided exclusively by their professional qualities, and not by personal or family loyalties. I’m speaking about this without any regret, because in actuality I really do love what I’m doing now.

“I wanted to return to Russia”

– Are you trying to convince relatives to get themselves over to the States? Your sister, for example…

– I’m trying, I’m trying. But she’s resisting. For the last two grades of school she was studying abroad, but she decided to go to university in Moscow and she returned to Russia, exclusively out of patriotic considerations. And I understand her perfectly well. I had more or less the same attitude in 2003.

– You also didn’t intend to remain abroad?

– I even had a ticket home. I was planning to come back to celebrate the new year in 2003. This was already after 25 October. I still kept foolishly hoping that everything would get better, that everything would be normal (Pavel’s voice noticeably wavered at these words – author’s note). Then my father communicated to me through lawyers that things were a lot worse than he’d thought and that it wouldn’t be a good idea to come back.

– Do those who surround you in New York know that you are Mikhail Khodorkovsky’s son?

– Until 2005, people in the USA had only a vague notion of who Khodorkovsky was and what he’s in jail for. My last name didn’t elicit any reaction back then. But in 2005, after the first verdict, when it became clear that they wouldn’t be releasing my father, this case began to resonate widely abroad. And when a new case was opened in 2007, the story became even more widely known, and people did indeed start to react to my last name. I don’t want to paint the situation in overly rosy colors here: there was negativity at times as well. American academics, who know the history of privatization in Russia very well, have a bad attitude right from the start towards the oligarch class, which appeared in that period. They regard both the first and the second of my father’s cases with a great deal of skepticism. But this is a rather not-large group of people.

– What do you think, do the residents of Karelia know the essence of what’s happened with your father?

– I think that these days they know already.

– We attempted to communicate on this topic with residents of Karelia, and it became clear: few have a grasp of your father’s case. Furthermore, many don’t want to know anything.

– My father can correct this situation better than others can – which he is doing. He’s recounted on many occasions that people in the colony turn to him for legal assistance. After 9 years, he’s managed to pick up some legal experience; therefore, when people don’t have the opportunity to consult with a lawyer, he can help them out, give advice, write up a basic complaint, submit an appeal, or draw up a simple set of documents. I think that people are going to hear about this in time, and get interested in my father’s case.

Karelia has allowed for a phone connection

– The opposition has gotten activated in Moscow. People have begun to more actively express distrust in the ruling power. In Karelia in this regard – silence. What, from your point of view, might be able to shake up the backwoods?

– Only the success of new people in local elections is capable of doing this. The main reason why “United Russia” continues to rake up insane percentages at elections consists of the fact that the people who have doubts about the competence of the powers have exactly the same kind of doubts about the competence of the opposition, and they simply don’t come to elections. They’re not ready to give their vote to “United Russia”, but neither are they ready to vote for some kind of opposition candidates.

– You organize actions in defense of your father in New York. Why? Do you truly believe that this can somehow influence the situation?

– From a rational point of view, the actions that we conduct here are not going to be able to free him. But this is that not-large contribution that I can make. You know what else is important for me? I haven’t been home for nine years. I don’t travel to Russia out of considerations of safety. Therefore, for me it is important, being here in the USA, to participate in opposition actions and in actions in support of my father. Well, so that I’d have the moral right to comment, to speak on this topic.

– You’re always talking about how you fear returning to the motherland. What are you afraid of?

– I’m afraid of becoming an instrument for putting pressure on my father.

-But Mikhail Khodorkovsky has another three children in Russia, after all, and any one of them could become this instrument. Why wait for you?

– We’ve got a rather clear-cut separation within the family on account of who appears publicly with announcements, and, without a doubt, this is a less dangerous kind of thing for me to be doing, inasmuch as I live in the USA. My grandmother, of course, finds herself in a totally different situation, but she’s just a very courageous person, and consciously interacts with the press and is not afraid.

Putin has got two perfectly concrete objectives. One: to hold my father behind bars while he’s in power, so that no potential catalysts for the opposition movement might emerge. The second: to obtain an admission of guilt. For Putin this is the last little hang-up, with which he wants to crush his opponent all the way. My father is never going to go for this. Therefore, any problems that might arise for me or for my sister or grandmother might be aimed specifically at beating out an admission of guilt.

– Your relatives are constantly shuttling back and forth between Moscow and Segezha. How do you communicate with your father?

– Until his transfer to the Segezha colony, we only corresponded by letter. Now we also talk on the telephone. And because of this I’m grateful that my father finds himself specifically in your place, in Karelia. I didn’t have an opportunity to call before. It has appeared exclusively thanks to the way things have developed over time over there at IK-7.

A naïve position

-Your father has been behind bars for 9 years already. Has he changed over this time?

– When you’re communicating with a person over a long distance, it’s hard to understand how his character has changed, but from the way he speaks and the things he’s writing about I am nevertheless compelled to believe that he’s become a softer person.

– And he used to be…?

– He used to be very tough. Without a doubt he remains that way now as well. But I think that after what he’s had to live through (the destruction of the company he’d dreamed about his whole life, responsibility for those people who were forced to abandon Russia, and a series of other emotional stresses), let’s just say that now he’s started to take account of the human factor.

– What has changed in relation to you?

– My upbringing was always based on one important postulate: “I don’t make any decisions for you; you do what you want to do, I’ll help you, but I won’t take any responsibility for your decision”. I asked him to recommend a university or a profession. No, no, no. No way, never. Now he’s begun to take a much more active part in my life; he’s begun to give advice.

– Not too late?

– I’m 27. Of course it’s a bit late. But better late than never.

– In one of your interviews, I stumbled across information about how when you were at school, you were upset with your father because you said he wasn’t exactly lavishing you with money. An unexpected detail.

– Ah, yes, yes. I think I know where you could have found out about this. Well, what can I tell you? I was studying in a Swiss school from grade 9 through 12. There were all kinds of kids there. There were children of very rich parents who weren’t particularly spoiled. I was one of those. There were children of not very rich parents who were very badly spoiled. Of course, childhood “that’s-not-fairs” would come up when you see an 18 year old kid getting the latest model of the “Mercedes” company’s sports coupe for finishing grade 12. There was a certain dissonance. My father just took me on a one-day trip to Berlin as a present.

– When did you see your father the last time?

– I saw him the last time in the USA at the end of September 2003. He happened to be in the States then. This was his last trip beyond the border before he returned to Russia. He stopped by for one day in Boston, to take a look at my university. The two of us had literally one evening together. He flew off the next morning already.

– Do you think that Mikhail Borisovich has regretted that he returned to Russia?

– No. Not in the least. He was convinced that he would be able to win as long as there was an open trial. Now we understand that this position was naïve.