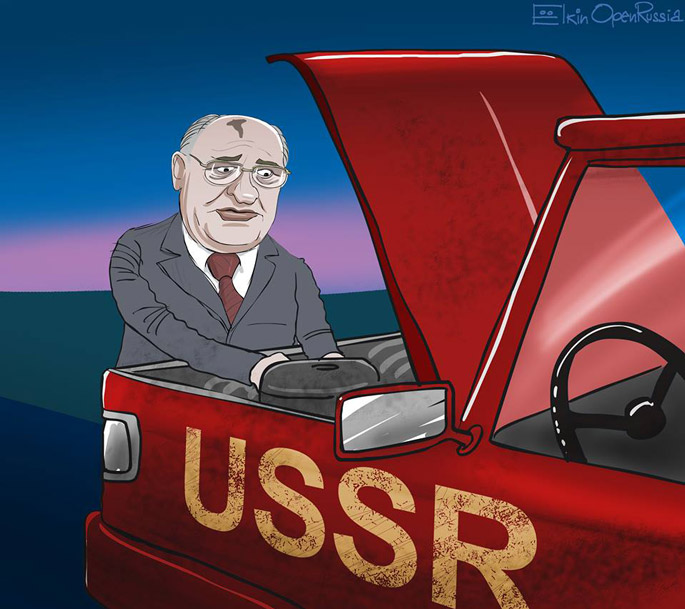

Perestroika 2.0

Perestroika 2.0

Mikhail Gorbachev has turned 85. But this isn’t the only thing that has thrust the last leader of the Soviet Union back into the limelight.

Gorbachev and his political era continue to be widely and variously discussed in Russia. As far as supporters of the current regime are concerned, he is unequivocally an enemy. The film director Nikita Mikhalkov, a personal friend of Vladimir Putin’s, recently appeared to suggest that Gorbachev should actually be tried: “Gorbachev and Yeltsin’s crimes [must be] recognised at the state level. [These politicians] committed a genuine crime. Whether they did so deliberately or not, whether they were motivated by ambition or not – that isn’t the issue here. Their achievements led to the collapse of our country! And this is the greatest geopolitical catastrophe to have occurred over the course of this century.”

It’s clear to see why the Kremlin should be exercised about Gorbachev. Despite backing certain of the regime’s policy decisions, such as the annexation of Crimea and Russia’s military operation in Syria, Mikhail Gorbachev is nonetheless unmistakably an opponent of today’s Kremlin leadership; for everything Gorbachev had spent his life struggling against is now coming to pass under the rule of Putin. “I’m a man of freedom. Freedom of choice, freedom of religion, freedom of speech – they can shoot me if they like, but this is something I won’t renounce,” he declared in a recent interview. Even if these words weren’t intended as direct criticism of the regime, they can only sound like a rebuke to the Kremlin.

In fact, Gorbachev’s entire biography spells inconvenience and danger to the Kremlin – as his birthday interview with Novaya Gazeta serves to confirm.

For the Kremlin, genuine freedom of speech is anathema. Not for Gorbachev.

Gorbachev: “Having instigated perestroika, we advanced step by step, taking our time; we got criticised for this, but we just kept going. And we reached a point where people finally realised that they had a constitutional right to speak, to ask questions. We all know that in those days even a perfectly straightforward yet spicy anecdote could mean a one-way trip to some far-flung part of the country. Glasnost was the queen of democracy – glasnost engendered freedom of speech and freedom of opinion … In a word, society started dealing with its own problems, playing a part in their resolution. Of all the things we achieved, this, for me, is the most important.”

The Kremlin is not interested in the people; the Kremlin is interested in an electorate amenable to manipulation. For Gorbachev, a well-developed civic consciousness represents an absolute value.

Gorbachev: “The most important thing is for people to get a sense of their status as citizens. If this sense is lacking in society, there can be no suitable foundations for democracy either. When they say, ‘we’re not ready,’ or ‘our nation isn’t sufficiently mature for democracy,’ we must understand that it’s not the people who aren’t ready, but those who’ve muzzled them. Now, incidentally, the problem has become acute once again: democracy is under attack in Russia.”

The regime’s overriding objective is to perpetuate its power ad infinitum. Gorbachev found the strength to depart the scene of his own accord.

Gorbachev: “You know that no one fired me. I did it of my own volition. […] I made the announcement because I could see that we needed to stop short of civil war. Which we weren’t far away from. There are higher interests, after all – people’s lives, the lives of current and future generations. All this calls for a very serious approach to things. Timely retreats can win you battles. I didn’t retreat, I decided to just leave. I don’t know – perhaps I was wrong, but I don’t believe that’s the case. What is a putsch? An overthrow, an insurrection – and the 1991 putsch served as a demonstration of the fissure in society, in the party, in the Politburo. It was a dangerous situation. Events with serious consequences for people’s lives could have been set in train.”

The Kremlin is markedly aggressive and preaches isolationism. Gorbachev invokes the values of peace, not those of war, and finds the country’s “closed-off-ness” unacceptable.

Gorbachev: “In order to achieve success in perestroika – and indeed life in general, irrespective of any slogans – you need peace. And only then can you think about education, good healthcare, social protection and so on. So you have to create international conditions conducive to the development of society. […] Which is what perestroika achieved. We signed important agreements with the Americans and eliminated a huge proportion of our nuclear arsenal.”

The Kremlin tolerates only notional political diversity. Gorbachev has always advocated the genuine kind.

Gorbachev: “My beliefs shone through in my proposals. It was necessary for the country. People had neither democracy nor normalcy. They were banished from politics and from everywhere else. They were just the hostages of ever-changing elites.”

If these words had been spoken by anybody other than Gorbachev – a man who would appear to be untouchable – that person would soon find himself in the crosshairs of the government’s snipers. As it is, his words act as a counterweight to the anti-democratic, anti-social, pretty much anti-everything regime.

However one views the Gorbachev legacy – and in many ways it is still too early to judge – once the current regime departs the scene, some sort of label will have to be invented for the country’s new democratic transformation – and “Perestroika 2.0” could well make the shortlist of potential names. In any case, the architects of a future “restructuring” (whatever it might be called) will need to heed the experience of Perestroika 1.0, for freedom of speech and reconciliation with the West will once again serve as their twin points of departure.