Putin’s Election Grip Is So Tight Even His Nemesis Can Take Part

The last time Vladimir Putin’s political party won national elections, ballot-stuffing allegations sparked the biggest protests of his rule.

Five years on, Putin appears to be so confident in his hold on power that even his most dogged adversary is welcome to challenge United Russia in next month’s parliamentary polls — Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the London-based former oil billionaire who was charged with murder in absentia in December.

Khodorkovsky, who spent a decade in prison, is back doing what he says got him jailed in the first place: supporting Putin’s opponents. All but one of the 19 candidates he’s grooming have been accepted by authorities overseeing the vote. Since being freed in 2013, Khodorkovsky has vowed to use what’s left of his fortune to hasten the end of the Putin era, though he admits the Kremlin’s grip on the electoral process is so strong it has nothing to fear, for now.

“Things are so tightly controlled that even a mouse couldn’t sneak past,” Khodorkovsky, 53, said by e-mail. “So there’s plenty of scope to find a middle path between free and fair elections and totally rigged ones.”

Senior Kremlin officials and advisers agree. Putin’s continued popularity, mastery of the airwaves and changes to the way lawmakers are picked all but guarantee United Russia’s victory in the Sept. 18 ballot, even amid the longest recession and steepest decline in wages in two decades.

Sergei Markov, a political consultant to the Kremlin staff, said the bigger goal is to ensure that the contest be viewed as legitimate in order to deprive the opposition of a rallying cry for mass demonstrations that would give it momentum going into Putin’s own re-election bid in less than 19 months.

“Not only are the authorities not preventing the Khodorkovsky candidates from running, they even appear to be helping them,” Markov said by phone from Moscow. “The key thing is to avoid tainting the results because this poll is seen by the opposition as a springboard for challenging Putin’s future win.”

Khodorkovsky said he’s mentoring candidates through his Open Elections project, which offers strategic, legal and organizational aid, but not money, which would violate rules on overseas funding. One of them, Maria Baronova, said the main hurdles she’s faced are financial — squeezing friends and family for loans to pay for posters and other mainstays of grassroots campaigning.

“There’s no reason to hide that you’re with Khodorkovsky,” said Baronova, a 32-year-old rights advocate for the exiled tycoon’s Open Russia foundation.

No Worries

If Putin, 63, is concerned Russia’s economic woes or public frustration with corruption will translate into protest votes, he’s not showing it.

In March, he named a veteran human-rights campaigner, Ella Pamfilova, to run the Central Election Commission, replacing an incumbent who oversaw the 2011 vote that was marked by what then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called “troubling practices.” Last month, Russia invited another critic of that election, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, a governmental watchdog, to send 500 observers to monitor the next one.

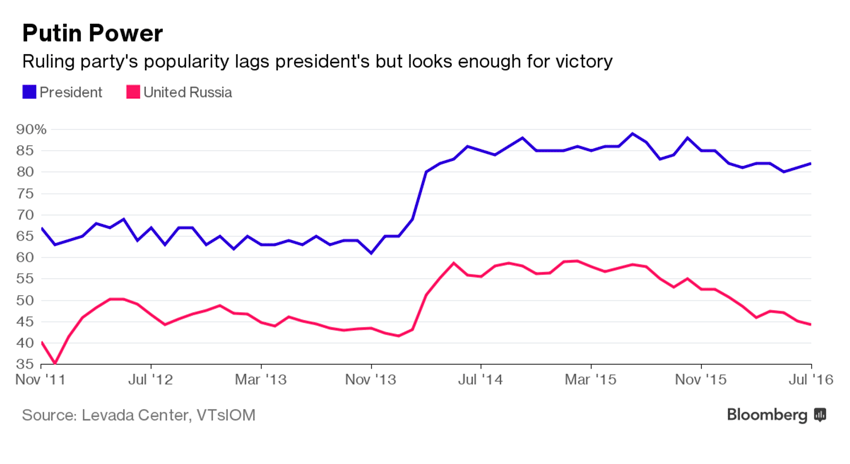

Last time, United Russia gained a comfortable majority in the State Duma, 238 of 450 seats, though it won just 49 percent of the official tally. Its support has since dropped to between 39 percent and 44 percent, the latest surveys by the independent Levada Center and state-run VTsIOM show.

Yet the party, which is headed by Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev, Putin’s longtime lieutenant, may still gain seats. Unlike in 2011, when all mandates were awarded to parties in proportion to their share of the vote, half will go to the winners of individual races. This gives United Russia an overwhelming advantage in “administrative resources,” such as state entities pressuring employees how to vote, so there’s no need to falsify results, said Nikolai Petrov, a professor at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics.

‘Manipulate Yes’

“The Kremlin’s slogan is ‘manipulate yes, falsify no,’” Petrov said. “The aim is to get the maximum amount of seats while avoiding scandal and conflict.”

Putin’s administration is already preparing for victory. The Kommersant newspaper reported this week that authorities are considering promoting the first deputy head of the Kremlin administration, Vyacheslav Volodin, to speaker of the Duma after the elections. Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov didn’t respond immediately to a request for comment.

United Russia may even end up with the two-thirds majority needed to amend the constitution, like it had when the presidential term was extended to six years from four in 2008, according to Alexei Makarkin, deputy head of the Moscow-based Center for Political Technologies. A Putin victory in 2018 would give him a second-consecutive term, the most allowed by law, for a second time. After serving as president twice from 2000 to 2008, he swapped jobs with Medvedev before returning to the Kremlin with a six-year term in 2012.

Paramilitary Force

When Russia last had single-mandate districts in parliamentary elections, in 2003, United Russia gained a super majority with less than 38 percent of the vote, which was crucial for Putin at the time because he was just starting to consolidate power, Makarkin said. Now the issue is largely superfluous because two of the other three parties in the Duma are loyal to the Kremlin, he said.

Still, Putin is taking no chances. In April, less than a month after shaking up the election commission, the retired KGB colonel created a paramilitary force of more than 340,000 troops that reports directly to the president and whose tasks include suppressing protests like those that erupted after the 2011 vote.

A leader of those rallies, former deputy premier Boris Nemtsov, was shot dead near the Kremlin in February 2015, just two days before he and another leader, Alexey Navalny, planned a march against the war in Ukraine. His murder remains unsolved. Navalny has been barred from running for office by two criminal convictions on charges including fraud that he says were trumped up. He’s appealing in the hopes of being allowed to run for president in 2018.

Wrong Direction

While Putin enjoys a personal rating of more than 80 percent, 37 percent of Russians say the country is headed in the wrong direction, according to Levada. A drop in commodity prices and sanctions over Ukraine are taking a toll. Millions of people have fallen below the poverty line in the past two years and the government, struggling with the widest budget deficit since 2010, has been forced to freeze public-sector wages and curtail pension increases.

Even with a dire economy, it’s difficult to compete against the crushing machinery of the state, according to one of the country’s oldest pro-democracy parties, Yabloko, which missed the 7 percent parliamentary threshold in 2011.

“Free and fair elections aren’t only about transparency in ballot-counting — but also access for political parties to the mass media during the entire period between elections,” Yabloko said in an e-mailed statement.

Sex Tape

One of United Russia’s most vocal critics, Mikhail Kasyanov, who heads the Parnas party, knows the power of media first-hand. In March, state television aired a video of the former premier having an adulterous romp with a subordinate, igniting a heated debate that exposed deep rifts among the opposition.

But even Kasyanov said Parnas has had “no problems” fielding about 280 candidates, including almost all of Khodorkovsky’s acolytes.

Alexander Oslon, who heads the state-run Public Opinion Fund, said the Kremlin is doing everything possible to avoid the mistakes of the last election, when smartphone videos of ballot-stuffing and other clear examples of vote-rigging spread through the Internet and prompted thousands of Muscovites to take to the streets. Those demonstrations rattled Putin, who directed the blame at Clinton, accusing her of sending an activation “signal” to “some actors” inside Russia.

“These elections will be a lot cleaner than in the U.S.,” Oslon said. “That’s called evolution.”