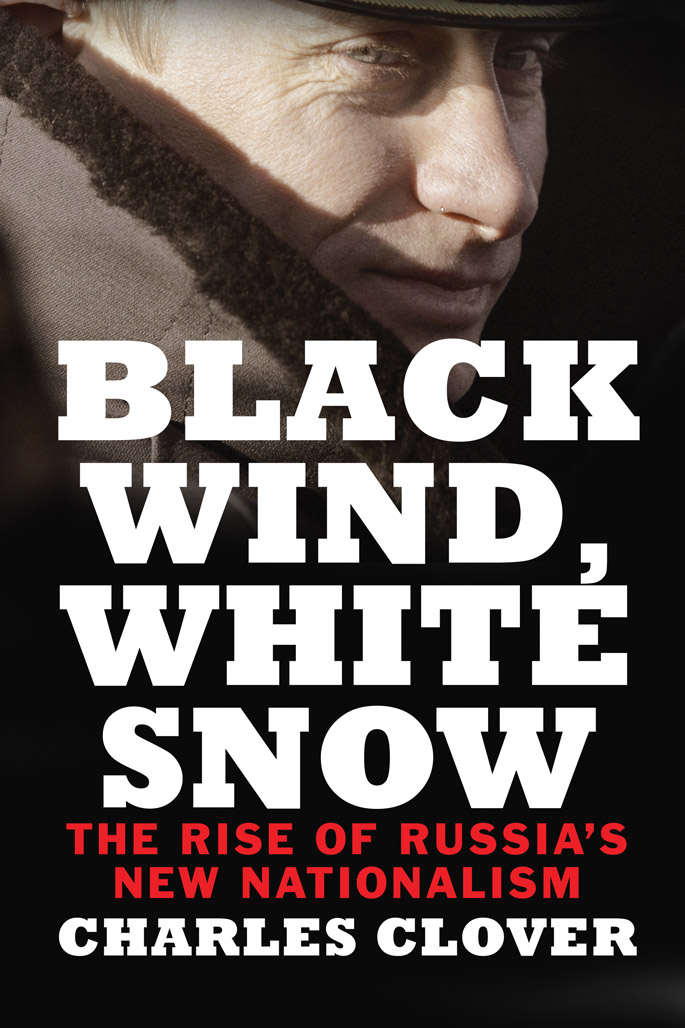

Review: “Black Wind, White Snow: The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism” by Charles Clover

In his new book, Charles Clover, Moscow bureau chief of the Financial Times from 2008 to 2013, writes about the new Russian nationalism, and the rise of “Eurasianism,” a theory of geopolitics, which is now popular in Russia.

Rodric Braithwaite

Looking at Eurasianism, that geopolitical theory, which sometimes colours the message put out by the Kremlin, Charles Clover has done a vast amount of research and has interviewed many of the main players, some of them very bizarre.

Eurasianism owes something to the theories of the British geopolitical theorist Halford Mackinder, who wrote in 1919: “Who rules East Europe commands the Heartland; Who rules the Heartland commands the World Island; Who rules the World Island commands the World.” It was a formula for a clash of civilisations between the great continental empires and the sea-borne empires of Britain and America, which appealed among others to ideologists in Nazi Germany. Since then many Russians have identified the “Heartland” with their own country.

But even before Mackinder devised his formula, the Russian linguist Nikolai Trubetskoi and his colleague Petr Savitski were developing the thought that Russia, straddling Europe and Asia, was destined to follow a unique path of its own. The theory was developed among a group of Russian émigrés in the nineteen twenties, and elaborated in the Soviet Union by Lev Gumilev, who spent some time in the Gulag, and was the son of the poet Anna Akhmatova and her husband Nikolai, who was shot by the Bolsheviks.

Lev Gumilev’s rambling books were published in the last years of the Soviet Union. They were taken up by a ragbag of right-wing intellectuals, such as the somewhat unhinged Eduard Limonov, the brilliant nationalist author Alexander Prokhanov, and the formidable Alexander Dugin. Dugin was a journalist and anti-communist dissident in the 1980s. He dabbled in the politics of the new Russia, advising the Communist party, setting up a fissiparous National Bolshevik Party, and developing a quarrelsome, erratic, but sometimes intimate relationship with the government of the day and its more shadowy agencies. He wrote prolifically and ferociously: among many other things, “Fascism – Borderless and Red” in 1997, an article in which he proclaimed, “In Russia we have been through two ideological stages – Communist and liberal. There remains Fascism;” and in the same year a major book, The Foundations of Geopolitics, which became a textbook in the Russian General Staff Academy where he now lectured.

Eurasianism is neither coherent nor scientifically based

Eurasianism, both in Dugin’s version and in those of his predecessors, is neither coherent nor scientifically based, despite the efforts of Trubetskoi and his fellows to make it so. It is an unimpressive ragbag of prejudices and national myths, nothing like as intellectually compelling as Marxism. In its windy generalities it resembles more closely the ideologies of the Nazis and the Italian Fascists, though its origins are quite different. Along with a revival of Russian Orthodoxy, it helped to fill the emotional and intellectual gap left by the collapse of Communism and its Marxist ideology. It appealed to a generation of Russians traumatised by the humiliation of the Soviet collapse: the loss of status, the loss of empire, the near disintegration of the state, the explosion of poverty, the endless lectures on good behaviour from the rest of us, the disdain for Russian interests as the Russians themselves perceived them, illustrated by the enlargement of NATO and the wars in Yugoslavia.

Clover spells all this out in fascinating detail. He devotes less time to the antecedents of Eurasianism that lie deep in Russian history. At the end of the first millennium, Kievan Rus could claim to be as sophisticated as any of its contemporaries to the West. But Kiev was destroyed by the Tartars in the thirteenth century; and the leadership of the Eastern Slav world passed to a small town in the Northern forests run by a family of minor Kievan princelings. The relationship between Muscovy, later imperial Russia, and the rest of Europe became one of playing catch-up, combined with much discomfort at having to adapt to the alien ways of a world perceived as heretical, rationalist, legalistic, coldhearted and hypocritical. Peter’s leap forward was seen by many Russians – including Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and a bunch of Slavophiles – as a betrayal. As the poet and diplomat Fedor Tyutchev told his colleagues in the Russian foreign ministry.

However you abase yourselves before her,

Europe will never give you her respect:

For in her eyes you always will remain

Not servants of enlightenment, but serfs.

Those extreme ideas may also be a rather desperate way for Russians to make sense of their history

Dugin’s Eurasianism and other less extreme ideas now popular in Russia are, perhaps, another reflection of that demand for respect, expressed by Peter the Great after his victory over the Swedes at Poltava: “We have come out of the darkness into the light; and people who did not know us now do us honour.” Those ideas may also be a rather desperate way for Russians to make sense of their history, of the epic triumphs and reversals of one of the world’s great nations, a country great by the traditional measures of power and artistic creativity, but one which has had more than its share of disaster at home and abroad – the Tartar yoke, the Time of Troubles, national defeat in 1856 and 1917, revolution, civil war, the Gulag, the Soviet collapse, and a tradition of domestic repression.

What matters about Dugin and his ideas, however, is less what ordinary people think about them, but what hold they have on the Russian government and its policies. His ideas remain popular in various corners of the system, and they have been invoked to support policies such as the annexation of Crimea and the move into East Ukraine.

In 2013, Vladimir Putin called Russia a “civilisational state . . . a project for the preservation of the identity of peoples [and] of historical Eurasia in the new century.” But Dugin’s ideas are far from having become the ruling ideology of the regime. Putin himself may be a nationalist but he is not an ideologist: there is no set of misty ideas woven into the regime and emanating from the Leader, as there was in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Putin picks up ideas when he thinks they are useful, and discards them when their value is no longer apparent. Dugin got cross with him when he failed to create “Novorossia,” the Russian province carved out of Ukraine, which Dugin and those like him had pressed for so energetically. Putin has the responsibility, and so far he has known when to stop. For all the noise he makes, Dugin has remained a marginal political figure.

But the new Russian nationalism for which Dugin speaks is entirely genuine. Clover casts a considerable light on its roots, on its passionate bias against the West, and on the Russian reality with which the rest of us now have to deal. His is therefore a book that needs to be read.

Black Wind, White Snow: The Rise of Russia’s New Nationalism by Charles Clover

Yale University Press, 304 pages

From 1988 to 1992 Sir Rodric Braithwaite was British ambassador in Moscow, first of all to the Soviet Union and then to the Russian Federation. Subsequently, he was the Prime Minister’s foreign policy adviser and chairman of the UK Joint Intelligence Committee (1992–93).