Talking of library and telephone exchange protests …

Talking of library and telephone exchange protests …

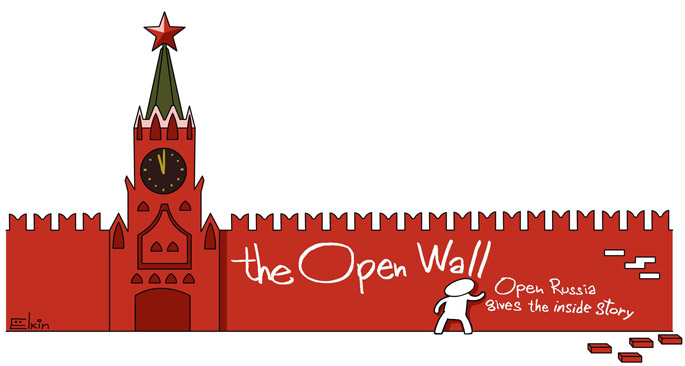

If you think that Russians have limitless reserves of patience, and have forgotten how – or are too afraid to – protest, what happened last week in Moscow shows how wrong we have been.

It began when three hundred people arrived at a district library under threat of being turned into offices for the Investigative Committee (the library is named after Dante Alighieri – so, naturally enough, witticisms about “circles of hell” have been circulating online). The crowd was livid, raising hell and booing the somewhat discombobulated officials, who were unable to explain why the Investigative Committee needed to commandeer a working library, when half of the offices in the city are empty.

Exactly a day later, several hundred people braved the cold April wind and rain to gather by a 1920s-era constructivist building in central Moscow; this edifice is a former telephone exchange earmarked for demolition by developers, who plan to replace it with a hotel and apartment complex. The crowd was headed by a municipal deputy, and, once again, people were incandescent with anger.

According to an elderly local resident, the demolition-threatened building was hit by a German bomb during the war. “The Moscow authorities are now worse than the Nazis,” she said, drawing a roar of approbation from the crowed. Provocateurs – big strong youths in tracksuits and hoodies – tried to sabotage the protest meeting … only to be driven off by the people, who threatened to turn them in to the police. Retreating, the hooligans lit a smoke bomb and threw rocks at the condemned building.

Both these events – most noticeable for the political passions of the crowd in the library (usually a haven of peace and quiet) no less than the altercations (we might almost call them street clashes) over whether a concrete box should be regarded as a cultural monument of constructivism – can be said to represent the true pulse of Russian civil society. As inexorably as grass growing through the asphalt, this pulse is making itself heard through the miasma of Russian society.

What happened in both cases was a popular gathering. The English word “rally,” which denotes a large-scale event involving a stage, police barriers, and, most importantly, protracted and painful advance negotiations with the city authorities as to the time and venue, is not appropriate here. No, these incidents are best described using the Slavic word skhod, which immediately conjures the idea of a specifically popular democracy.

Despite the fact that the government, in the wake of the 2011-12 protests for fair elections, has spent much effort tightening legislation on the rights of citizens to protest, Muscovites effortlessly bypassed these barriers in both cases: on the first occasion, they simply gathered inside the library, while the second was formally a meeting with a municipal deputy; and in neither case did the police interfere.

Needless to say, neither the Dante Alighieri Library nor the telephone exchange building are in themselves the crux of the issue here (though the former really does boast a fine collection of antique Italian books, while the latter is a genuinely handsome edifice); no, what really matters is that civil society is being kept alive. When something of this ilk occurs, expert communities quickly get involved, while members of the public write open letters, organise paper and online petitions, hold pickets and gatherings; people have remembered they’ve deputies to call upon, and, much to the surprise of the latter, they’ve actually started writing and phoning and making demands. These regional stories are being enthusiastically and meticulously debated on Facebook, the primary samizdat (self-publishing) platform of our age; furthermore, independent media outlets – and, increasingly, state-owned ones as well – are sending correspondents to these gatherings. In short, they’re becoming big politics.

The results are no less consequential. The defence of the library has already yielded fruit: at least for now, the eviction order has been cancelled, meaning that all these petitions and gatherings were not in vain. This is really breaking the mould. What we’re witnessing isn’t merely the development of a political space for protest, but the materialisation of healthy patterns of social and civil behaviour: if you see injustice, protest against it and make your own truth heard. Which is fundamentally at odds with the behaviour inculcated in the Russian public in the wake of 2011’s election fraud.

Admittedly, it’s not yet clear whether we can claim victory in the telephone exchange affair (the building was rapidly covered with scaffolding immediately after the gathering), but an early good sign is that the story has been featured on a federal channel. It’s uncertain, too, whether the defence of Dubki Park in north Moscow will prove successful (dozens of people have clashed with private security and police in an attempt to prevent construction there). But let us be clear about one thing – the will is there.

Given the restrictions that have been increasingly placed on us, there is something so wonderfully symbolic about these library and telephone exchange protests – you can’t stop people reading and talking … Of course, it could well be that these and similar protests will end in failure; whatever their outcome, however, they are already shaping the civil society and political landscape of a future Russia; and no future democracy would be possible without them. Who knows, perhaps some day – a century from now, say – these defenders of libraries and telephone exchanges will even themselves be honoured with monuments.