The Conflict Intelligence Team versus the Kremlin

The group of Russian investigative bloggers known as the Conflict Intelligence Team, have been monitoring the military movements of the Kremlin, and making life considerably more difficult for the regime’s propaganda machine.

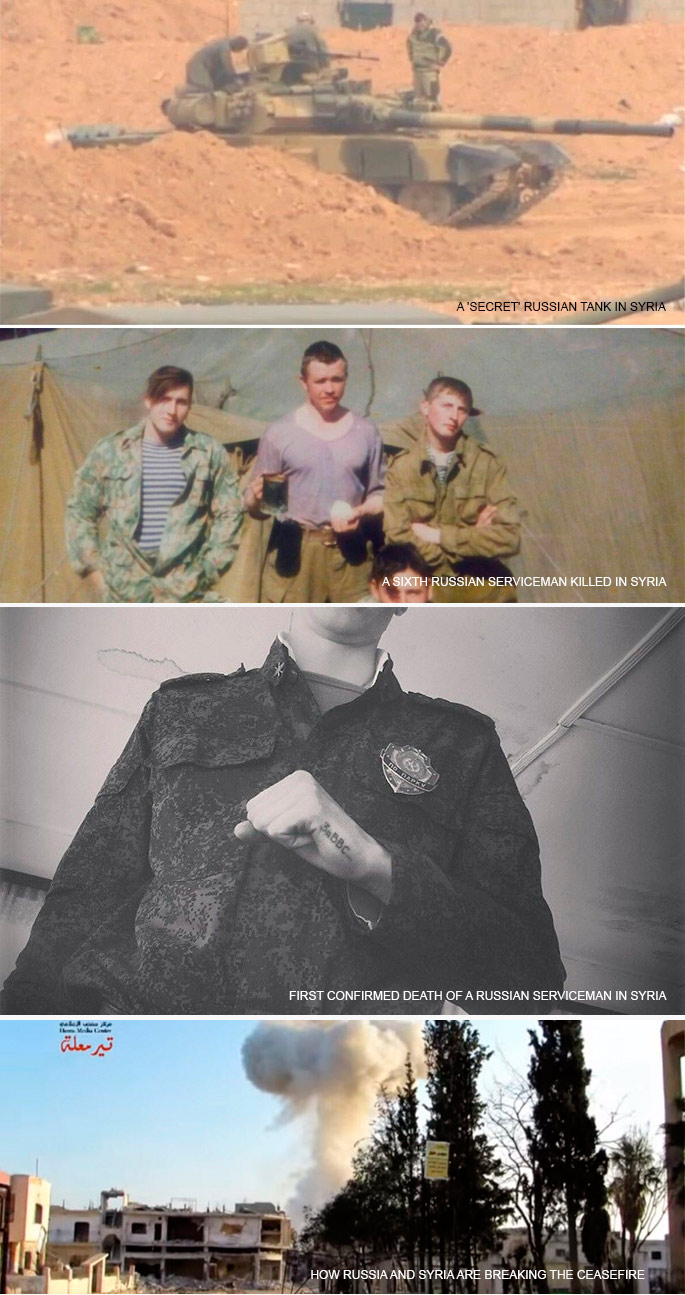

The Conflict Intelligence Team was inaugurated in May 2014, when activist Ruslan Leviev realised that the war in Eastern Ukraine called for a coordinated fact-finding mission: disparate civilian investigators, he felt, needed to join forces in order to exchange intelligence in an effective way. “It somehow panned out,” he recalls, “that by June or July 2014 we’d succumbed to this civic impulse and become a team.” If state television maintained that the Russians fighting in the Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics were exclusively volunteers, the investigators used photographic and video evidence as well as eyewitness testimonies and other publicly available information to prove that the Donbas was bristling with heavy Russian artillery and official servicemen. Ditto Syria: the official story may be that Russian aircraft have bombed Islamic State targets only, but the Conflict Intelligence Team has released evidence of attacks on moderate oppositionists and civilian targets.

Ruslan Leviev, the project’s creator, is twenty-nine years of age. He quit his law degree in his fifth year and – this being the pre-Bastrykin era – even spent a couple of years in the investigative bodies. He got his first taste of political activism in December 2011 when, on the day following the fraudulent Duma elections, participants of the opposition’s first protest rally were indiscriminately detained by police. Leviev, who had taken part in the protest, was on his way to the metro when they seized him, accused him of shouting “They all must burn!” – and threw him in jail for two days.

In an interview with Open Russia, Ruslan Leviev reveals that he is now much better equipped to deal with any mendacity on the part of the authorities, while the Conflict Intelligence Team has the capacity to continue operations even in the absence of its founder, should he face retaliatory measures by the regime.

How does an investigation work?

Ruslan Leviev In the case of Russian military fatalities, it all begins with our coming across an online post by a grieving relative who says that the deceased was killed in Ukraine or in Syria. We take this as a starting point and start gathering facts. We make contact with the deceased’s comrades-in-arms, relatives and friends; we then travel to wherever they’ve been buried, and that’s generally where we discover the clinching piece of evidence – a wreath from the Ministry of Defence, by the graveside.

When we’re investigating attacks on civilian targets or verifying whether our forces have been where they shouldn’t have been, our modus operandi is different. We’re constantly monitoring news outlets that report on Syria and Ukraine, and we invariably encounter video footage and stills that demand further investigation. In February, for example, a CNN correspondent said on camera that, just behind him, Assad’s troops were fighting to regain control of Palmyra. But, having thoroughly scrutinised the image, we proved that it wasn’t Syrian forces that were visible in the background, it was Russian. This was all happening in Raqqa province, where the presence of Russian troops was being denied at the time.

What criteria (if any) do you employ within the team to gauge the efficacy of what you’re doing?

We make active use of the “devil’s advocate” method, and go public with an investigation only when team members who’ve unearthed certain findings succeed in convincing the team as a whole of the veracity of their arguments. So you’ve got one person defending their position while the rest remain intentionally sceptical. Every “case” goes through the same process, and only three out of ten investigations end up being made public.

How many “cases” have been investigated by the Conflict Intelligence Team?

Around a hundred.

What have been your most notable investigations?

In May 2015, for example, we were investigating the deaths of three Russian special forces operatives in the Donbas. Minsk II was already in force at the time – everyone, Putin included, was ostensibly in favour of a truce, and suddenly three of our GRU special forces guys die in the Donbas. The world’s media devoted a great deal of attention to this issue.

We were one of the first Russophone teams to prove that our troops were being transferred to Syria. We went public with our investigation materials on September 5, and literally two days later there was a report on Russia-24, which accused me of lying, and denied that any forces were being moved anywhere. But our military operation officially began on September 30, our military contingent magically materialising in Syria within the space of a single day.

We were the first to report that Fyodor Zhuravlyov had been killed in Syria. Zhuravlyov was a special operations serviceman; in other words, we’d already proved back in November 2015 that Russian elite units were operating in Syria, and it’s only now, in March 2016, that Vladimir Putin has personally admitted that this is the case – that Zhuravlyov was indeed in Syria and that he’d been killed there.

Russian attacks on civilian targets in Syria

What case proved most difficult for you, and why?

That would be our first investigation into Russian attacks on civilian targets in Syria. Generally speaking, the Syrian conflict is many times more complex and convoluted than the Ukrainian – there’s a plethora of diverse factions in Syria, they’re all fighting one another, and it’s unclear who’s radical and who’s moderate. Furthermore, any given faction might be moderate today, but tomorrow it may well become radicalised and pledge allegiance, say, to Al-Qaeda. Investigating the airstrikes on Talbiseh, we endeavoured to prove that this town, which had frequently been changing hands, was under the control of Western-backed moderates on the day of the bombardment. We compared a lot of satellite data, looked at videos and stills of various Syrian factions, and communicated with Syrian activists. It was extremely complicated and took a lot of time and effort, but we ultimately proved that Russian planes had launched airstrikes against Syrian moderates.

Generally speaking, the Syrian conflict is many times more complex and convoluted than the Ukrainian

What can you tell us about Conflict Intelligence Team staff members? Who are these people by training and profession? What are their views and convictions?

The only person I can tell you something concrete about is Kirill Mikhailov, who’s been living in Kiev since 2014. He trained as a linguist so he’s the one who usually takes care of translation work and English-language interviews. Kirill has been actively involved in every oppositionist rally – for example, he was a citizen streamer during Occupy Abai [i.e., he did a live video relay of the event. – Ed.].

Did he leave to escape persecution?

Yes, he says the authorities were constantly threatening him and wanted to haul him off to jail. There was a whole wave of people fleeing the country back then – he wasn’t an isolated case. But the fact he left has nothing do with our investigations, which simply didn’t exist at the time. As for the other two members of the team, I know virtually nothing about them – not their real names, not how old they are, not even where they live or what jobs they do besides this one. I’m deliberately keeping myself in the dark. Given the fact that we might be searched at any time or have our technology confiscated, the best way of protecting [one’s colleagues] is simply not to know anything. The reason I trust these people is because I read some of their materials in May 2014 and saw that they were producing high-quality investigative work – and doing it clinically, without emotion.

And if you do suddenly fall victim to regime repression, it’s these anonymous guys who’re going to pick up the mantle and carry on the work of the Conflict Intelligence Team?

Let’s not forget that Kirill Mikhailov is a public persona. Otherwise, we’ve long had everything prepared for this eventuality. The team has complete access to my social media accounts, bank accounts, etc.

What do would-be volunteers tell you about the nature of their motivations? Why do they want to help you?

It all depends on what sort of volunteers they are. If they’re fellow-thinkers who share our goal of thwarting “the deleterious activities of the Russian regime” – activities that catalyse “the escalation of military conflicts” and lead to “military fatalities and the destruction of civilian populations” – they see that we operate efficiently and dispassionately, and thus want to help us change the situation in Russia.

But sometimes we’re also contacted by soldiers and militiamen who are directly involved in the fighting. We’ve now reached the point where we’re even getting offers of cooperation from Ministry of Defence officers and employees of private military firms who are fighting for Russia in Syria. These people usually tell us that they’re tired of the lies of their superiors – our troops’ involvement in the war is constantly being denied, but then you got soldiers coming home in coffins.

A lot of people have had enough of top-brass lies, then?

For every ten approaches by fellow-thinkers, we get a single approach from someone who, on the face of it, is more foe than friend, but who still wants to help the Conflict Intelligence Team. We’re currently working with five such individuals.

For every ten approaches by fellow-thinkers, we get a single approach from someone who, on the face of it, is more foe than friend

Together with several other activists, you lodged an appeal with the Russian Supreme Court against Putin’s decree to classify information on military casualties in peacetime. The decree was upheld by the Supreme Court in August 2015. Are you afraid that the new legislation might be used against the Conflict Intelligence Team?

Arguing in the Supreme Court with the president’s representatives, I saw just how broadly this decree was being interpreted. I’d previously understood the term “casualties” to denote either deaths or injuries. But they were contending that it encompassed absolutely everything – including soldiers’ psychological state. So if a soldier falls into depression following a special op, that’s classified information as well. So yes, the new legislation does, of course, pose a big threat – for the Conflict Intelligence Team included.

However, generally speaking, this decree applies to individuals entrusted with state secrets. Journalists and investigators may just be charged with treason instead.

How, in general, does the regime react to your investigations? Have you encountered anything in the way of pressure or persecution?

For the most part, they push back publicly: federal media, for instance, claims that I’m lying, that I’m doing it all for the sake of PR, or even that I’m working for Western intelligence agencies. But when, in February of this year, we were preparing to go public with our Debaltsevo investigation, in which the Russian Defence Minister featured personally, my social media accounts were hacked; after the report was actually published, my email account was hacked as well. Other than that, I’m constantly threatened with murder, violence and imprisonment – both over the phone and via social media.

I had a noteworthy encounter back in August 2015, when I was summoned to the military prosecutor’s office and questioned about one of our inquiries. After the official part was over, and I’d given them the requisite explanations and signed the protocol, the military prosecutor decided to discuss my Supreme Court appearance. He said outright that our activities violated certain articles of the Criminal Code and that I could be jailed at any time. This was a transparent hint: better stop doing what you’re doing, else you could end up behind bars. The prosecutor had absolutely no doubt that I could be jailed even that very day on the basis of our investigations.

Can you envisage a future where Russia’s foreign aggression is reduced to such a degree that there simply won’t be a need for your current operation?

Absolutely. We don’t believe the Putin regime is going to last forever. We think this whole scenario of Russian military expansionism won’t go on for longer than another two years – five at most. We’re preparing in advance for a situation removed from our current field of activities. We’re looking to develop into a professional and authoritative international organisation – one that might focus on investigating Islamic radicalism and terrorism, for example. We’re prepared to retrain – and have already started learning Arabic.