The Kremlin will have to live with HIV

The number of HIV-positive Russians is now over the million mark, and increasing. But the government is in denial.

Sergey Orlov

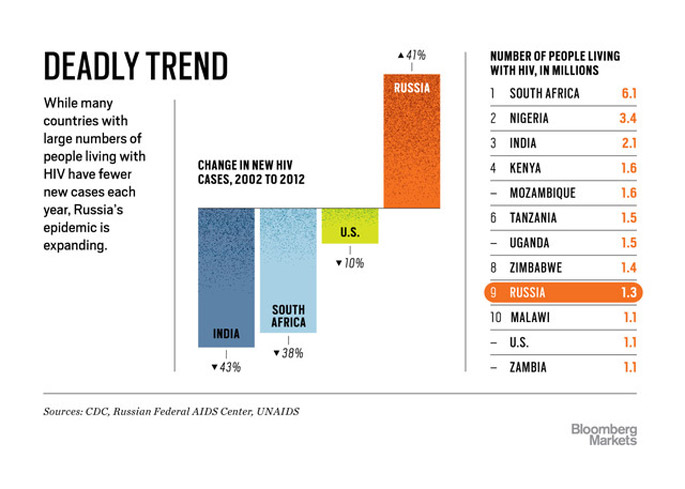

On 15 May, Russia, together with the rest of the world, remembered AIDS victims at the International AIDS Candlelight Memorial. When, at the beginning of 2016, it became apparent that the number of HIV-positive Russians is now over the million mark, Academician Vadim Pokrovsky, head of the Federal Scientific Research Centre for the Prevention and Control of AIDS, set Russia in the context of the rest of the world with the following disheartening statistic: “Russia has three times more HIV-positive people than the EU; twice as many as France and ten times more than Germany.” Meanwhile the Russian government, which refuses to see the current HIV situation as critical, explains airily that at some point in the future (all victories have been deferred until after the presidential election) it will strike a crushing blow at the disease, which is spreading all over the country.

America to blame – again

The HIV/AIDS day on 15 May split the Russian media: TV Rain invited people living with HIV to come and talk about their problems, but other media outlets, which are the majority and chiefly run by the state, concentrated on the campaign Stop HIV/AIDS, which was timed to coincide with the international day. The patron of the campaign is Svetlana Medvedeva, and the TV ‘picture’ it presented was very optimistic: there was no talk of an epidemic and no people with HIV took part, but every frame was taken up with endless students demonstrating their awareness by setting off in neat, fearless ranks to give blood.

Considering the bigotry and indifference of the Russian government, the Medvedev project is also, of course, a breakthrough with the promise of a favourable outcome – convincing people to have the test is no small matter. There is only one BUT: if a student from the TV programme suddenly tests positive for HIV, he will be of no more interest to state journalists who are highlighting Svetlana Medvedeva’s work – he will immediately become too much of a problem. The ideology of the ‘Second Lady’s’ project is that it is only aimed at people whose test results will be negative. Anyone unlucky enough to fail will get no help from the state media, and will have to search the internet to find Academican Pokrovsky’s data showing that “from 2011 the therapy budget has not increased, while the number of people being treated has grown by almost four times.” This means that there are by no means enough medicines in Russia for everyone, so “over the past five years the number of HIV-positive people has almost doubled;” and the lack of medication means that treatment is started only when “the HIV-positive person is under direct threat of developing AIDS.”

The ideology of the ‘Second Lady’s’ project is that it is only aimed at people whose test results will be negative

Data from the Anti-AIDS movement show that currently there are approximately 480,000 HIV-positive people in Russia with an immune count of less than 350 CD4 cells. The most antediluvian standards would rule that all of them need urgent treatment, but only 220,000 are receiving it; our thrifty Russian government is simply unblushing in risking the lives of the others, while declaring that by 2020 up to 90% of infected people will be receiving treatment.

If, however, government plans to restrain the virus come to nothing, it will always be possible to take the tried and tested path, and refer to external circumstances beyond our control. Russia’s former Chief Sanitary Inspector, currently assistant to the prime minister, Gennadii Onishchenko, does just that: “The flood-gates opened when the Americans sent troops into Afghanistan and opiates started being produced on a massive scale …”

“I really don’t want to die”

The World Health Organisation (WHO) considers that the best way of preventing HIV is treating those already infected: the more the virus is put under pressure by medication, the fewer opportunities there will be for it to spread in the future. Thus, someone taking his medicine carefully becomes virtually free from infection (statistics show that medication taken with 70% accuracy will result in a decline in the HIV RNA level of only 20%, but at 100% accuracy, the viral load almost disappears, falling by 98%).

For such results, one new-generation tablet need only be taken daily. But how is this possible if there are often simply no medicines of any sort? In order to survive, patients themselves track down the delivery of medicines to their regions, and publish their comments on a site with the eloquent name Disruption.ru. There are hundreds of messages from all over Russia:

“There are no medicines and the doctors don’t know when there might be, perhaps at the end of August … I really don’t want to die, but I only have 300 cells … I’m completely helpless and I feel like howling.” (Irina, Tula, 14.05.2016).

“I’m 7 months pregnant. Sometimes I get Nikavir, sometimes Tenofovir, depending on what is available. The doctor said that Tenofovir shouldn’t be taken during pregnancy, but there’s nothing else.” (Lemonad, Krasnodar, 15.05.2016).

“Today I went to Sokolinka, to the Moscow City Centre for Prevention and Control of AIDS. They didn’t take any blood because they haven’t had any chemicals for nine months. They gave me Olitid because there was nothing else and told me to buy medication myself. I don’t have that kind of money.” (Ksana, Moscow, 13.05.2016).

Until 2013, the Health Ministry purchase of HIV medicines was centralised, but for the last three years the regions have been purchasing for themselves. The results vary enormously, often because of corruption. “The variation rate over the regions between the minimum and maximum prices for one of the most popular and widespread drugs, Lamivudin, is 16 times. Generic drugs are more expensive than branded drugs in Russia, as can be seen at auctions, where branded drugs often win out, because they quote a cheaper price than the generics. Only in Russia can one find such nonsense,” says Denis Goldevsky, specialist from the Aid Foundation for AIDS.

This scandalous situation has been turned to his advantage by Sergei Chemezov, Vladimir Putin’s old friend

This scandalous situation has been turned to his advantage by Sergei Chemezov, Vladimir Putin’s old friend, and head of the extremely powerful state corporation Rostec. In the summer of 2015, he suggested the president should decentralise supplies and make Natsimbio, a subsidiary of Rosteс, the only supplier to the Health Ministry of several groups of medicines. Mr Chemezov was primarily interested in monopolising supplies of medicines for HIV, tuberculosis and hepatitis. The high-ranking official presumably explained away his somewhat immodest requests as being in the interests of the state: “it is essential to ensure that the Russian Federation maintains its sovereignty in the production of medicines and that import substitution can be guaranteed in the medicine sector of the domestic economy.”

Rostec appeared on the scene at exactly the time when the government planned to double budgetary expenditure on treatments for HIV/AIDS (up to 41 billion roubles a year). But for the moment the regions only see their expenditure on medicines being cut; the growing epidemic (i.e. the rapid growth of new patient numbers) and the appetites of Rostec itself will probably mean that HIV-positive people will not see any influx of new money.

Andrei Skvortsov, coordinator of the public movement “Patient Control” has a good idea of what import substitution can mean, especially when it goes hand in hand with a desire to economise: people will start being given toxic medicinal products with strong side effects, or medication such as Stavudin, which is banned by the World Health Organisation. “Russia produces some cheap medical products. The budget for treating HIV infections, in particular the purchase of antiretroviral drugs, is not growing. But, according to the Health Ministry, the number of people taking the therapy can increase by up to 60% a year. How can these people be put on the list for treatment? Only by decreasing the price of the products, and by buying in large quantities of cheap, old products, and moving everyone from expensive, quality plans over to the cheaper versions. That way, the number of infected people may grow, but costs will be reduced.”

“HIV will be taken over by Rostec and General Chemezov”

Rostec will corner the market for supplies of HIV medicines this autumn, but patients and experts do not rule out this new centralisation turning out to be either a different kind of chaos or a price free-for-all for the monopoly supplier. Rostec is in no hurry to clarify: “As soon as Chemezov took the initiative to set up a monopoly of supplies and wrote to the president, patient organisations started writing to the Health Ministry and to Natsimbio, asking that a plan of action should be published indicating what they are going to do, how they are going to supply the medicines, but nothing has been published. We know nothing about the names of the HIV medicines, or any of their plans,” says Denis Goldevsky.

At the end of last year, the chief editor of the Antiretroviral Therapy online project, Dr Ilya Antipin, advised his readers not to expect anything good from the arrival of Sergei Chemezov. “HIV will be taken over by Rostec and General Chemezov (Natsimbio is a part of this monster), whose greed has been legendary for a long time. Keep believing that Rostec will not let us down, though I would recommend as an emergency measure setting aside some hard currency each month, whatever you can manage, as supplies will inevitably and fatally deteriorate. The next year/eighteen months might be just about bearable, you’ll have to consider this as a bit of leeway that the government is giving you in the upcoming race for survival.”

The epidemic of the day before yesterday

Svetlana Medvedva’s Stop HIV/AIDS project has received the support of the Russian Orthodox Church, and on 15 May Patriarch Kyrill spoke on the subject. He first called on believers not to judge people with HIV/AIDS “no matter how that person acquired this misfortune.” Then he shared his views on how to avoid the disease: “Obviously we can do battle with this misfortune by giving our young people and the whole of society a sound moral education, by inculcating family values and the ideas of chastity and fidelity in marriage.”

Pavel Lobkov is a liberal journalist on TV Rain who has become an HIV/AIDS expert (having discovered that he was HIV-positive in 2003). He does not have much time for the patriarchal ways of avoiding the disease: “Near where I live there is one single shop, which sells packets of condoms at 600 roubles for 12. Opposite the shop is the Russian University for the Humanities, and its hostel with masses of young girls and boys. Every day, on my way home from work, I see couples buying champagne and looking at the condoms, but they see they’re 600 roubles, and don’t buy them because they cost the same as the champagne. The state could make condoms freely available in schools and institutes because, in a hostel full of 18-year-olds, heterosexual contact could spread the disease like wild fire.”

“I see couples buying champagne and looking at the condoms, but they see they’re 600 roubles, and don’t buy them”

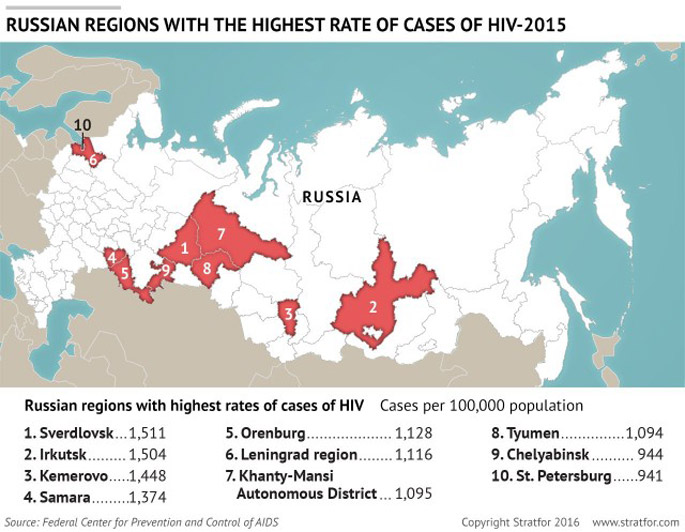

Currently one of the main questions about HIV concerns the epidemic: is there one, or not yet? Health Ministry officials are only making preparations for a worst-case scenario. The assistant to the Health Minister who deals with questions of HIV/AIDS is Dr Lyalya Gabbasova: she considers that, if there are no changes to the current ways of dealing with HIV infection, Russia will have an epidemic “in the next few years. We have twenty or more regions with very high levels of HIV infection, and it is always in these regions that the number of new cases is the highest. If we take the international assessment suggested by WHO, it is in these regions that the epidemic could start.”

Tash Granovsky, activist for the Anti-AIDS movement, cannot be doing with this official optimism: “These excellent officials keep on talking about the upcoming epidemic. What do they mean? Where? The last developmental stage of an epidemic is called a “generalised epidemic” [preceded by “low-level” and “concentrated”], the calculation for which is very simple – when more than 1% of pregnant women are infected. In Russia this was the situation in more than 20 regions in 2015. There’s no epidemic coming – it arrived the day before yesterday. Something has to be done now and a huge amount of work will be needed to do it.”

“There’s no epidemic coming – it arrived the day before yesterday”

The most disastrous situation is in the Samara and Sverdlovsk regions, where more than 2% of pregnant women are already HIV-positive. The barrier of 1% is exceeded in Kemerovo, Ulyanovsk, Irkutsk, Leningrad and another 13 regions. Moscow and St Petersburg are very close to being on the list. The generalised stage means that the infection is no longer limited by any groups of risk, and can be spread among virtually all levels of society.

It would, however, be a mistake to think that the problem is localised in 20 administrative areas of the Russian Federation. Bashkiria, for instance, is not formally on the list of regions affected by the epidemic, but this doesn’t make life any easier for the HIV-positive people there: “In Bashkiria the situation with tablets and tests is simply catastrophic: people change their medication frequently, and the most basic medicines are not available. Quite recently the HIV-positive figure in Bashkiria was 7-8,000 people, now it stands at 22,000 and these are just the official figures, the real situation is much worse. Our republic is back at the beginning of the 00s. We are in the Stone Age, as it were, as regards service, medication and access to treatment,” says Anna Dubrovskaya, president of the regional organisation “Voice Plus.”

There were nearly 95,000 reported new cases of HIV infection in Russia in 2015. Without an open discussion in the media about prevention, without sex education in senior schools, without regular access to modern medication for all HIV-infected people, or any serious discussion of replacement therapy for injecting drug users, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is heading only one way.