“Screw them”

President Putin likes to show that he hasn’t quite forgotten his thuggish upbringing when talking about the West, but perhaps he ought to be more wary of Western sanctions.

Yevgeny Karasyuk

The US and EU are mulling new sanctions against Russia – this time over Syria. Russia’s protests are becoming ever more sluggish, and, with sanctions now in place for over two and a half years, it is becoming clear that the Kremlin doesn’t regard them as a particular calamity – or at least claims not to. Discussions around the resilience of the Russian economy, hamstrung by cheap oil and Western restrictions, have become commonplace, and the resulting damage inspires not so much compunction as temerity in Putin’s officials. Particularly telling was the president’s recent outburst at the BRICS summit in Goa; when asked whether Russia would consider softening its retaliatory sanctions against Western countries – a move that could encourage Europe and the United States to re-evaluate the current regime – he riposted “screw them.”

Putin had previously stressed – and stressed repeatedly – the advantages of the current situation, claiming that both sanctions and countersanctions (or, in his words, “countermeasures to protect our market”) serve to benefit local businesses. One of the few sanctions-related anxieties voiced by the president concerned “restrictions on access to technologies.” But perhaps Putin simply isn’t taking everything into account. What, then, could he be overlooking? Consider the following four graphs.

![[Capitalisation of the Russian Federation and the world’s most valuable companies*] *As of 14.10.2016 Apple – $634 billion, Alphabet – $535 billion, Microsoft – $447 billion, Amazon – $387 billion, Russian stock market (Moscow stock exchange) – $380 billion, Facebook – $367 billion, Walmart – $212 billion Source: NYSE, NASDAQ, Moscow stock exchange](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Graph-11.png)

[Capitalisation of the Russian Federation and the world’s most valuable companies*]

*As of 14.10.2016

Apple – $634 billion, Alphabet – $535 billion, Microsoft – $447 billion, Amazon – $387 billion, Russian stock market (Moscow stock exchange) – $380 billion, Facebook – $367 billion, Walmart – $212 billion

Source: NYSE, NASDAQ, Moscow stock exchange

In March 2014, Russian stock indexes began to fall even before EU and US sanctions had actually been announced – the expectation alone was sufficient to prompt the decline. During the week preceding the announcement of the first wave of sanctions on March 17, the rouble-denominated MICEX index fell 7.6% and the dollar-denominated RTS by 8.3%, returning to 2009 levels – 2009 being, lest we forget, a crisis year.

In 2011, the capitalisation of the Russian stock market exceeded $1 trillion; it is less than $500 billion today

But that was just the beginning: the Russian market continued to fall, and, in December 2014, against a backdrop of plummeting oil prices, the situation became critical. Ten days into that month, the total capitalisation of the Russian stock market fell below that of Apple before being surpassed in mid-December by ExxonMobil, Google and Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway. In 2011, the capitalisation of the Russian stock market exceeded $1 trillion; it is less than $500 billion today. The government, hoping to transform the Russian capital into a global financial centre, had planned to increase the capitalisation of the Moscow Stock Exchange to 93% of GDP by 2014 (and to 100% in 2015). The reality proved three times worse than these forecasts.

![[Investment as a share of GDP] Source: Rosstat: Sberbank CIB](/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/Graph-21.png)

[Investment as a share of GDP]

Source: Rosstat: Sberbank CIB

Perhaps Putin is comforted by the idea that sanctions “are detrimental not only to the Russian economy but to the global economy as a whole.” At the same time, the president has declared, with his usual confidence, that “the Russian economy is an important sector of the world economy.” And yet, while the world’s economy has been developing steadily in recent years, Russia’s has experienced periods of moderate stagnation interspersed with profound dips.

And here’s the upshot of these divergent trends: ex-finance minister Alexei Kudrin expects Russia’s share of global GDP to decline to 2.6% by 2020. In 1992, this figure (calculated by purchasing power parity) was 4.9%, as compared to 3.3% in 2014. The trend could be reversed only in the event of a substantial increase in investment into the Russian economy, but, as the table above illustrates, the investment/GDP ratio has been steadily declining. According to a forecast by PWC, the Russian economy will grow extremely slowly in the coming decades, lagging behind even the likes of Colombia in terms of its pace of development.

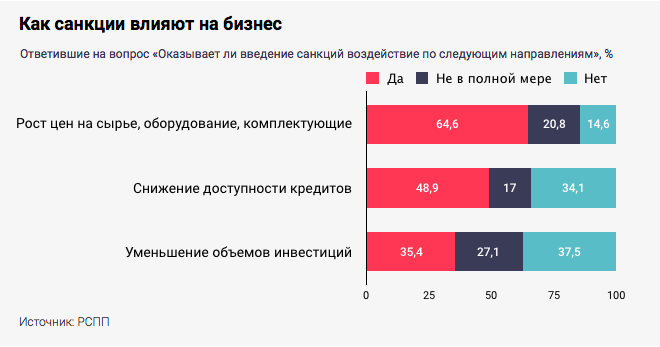

The impact of sanctions on business [RSPP survey]

Have sanctions contributed to…

…a rise in cost of raw materials, equipment, components?

Percentage breakdown of responses: Yes: 64.6%, Not definitively: 20.8%, No: 14.8%

…a reduction in the availability of credit?

Percentage breakdown of responses: Yes: 48.9%, Not definitively: 17%, No: 34.1%

…a lower volume of investment?

Percentage breakdown of responses: Yes: 35.4%, Not definitively: 27.1%, No: 37.5%

Source: RSPP [Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs]

The regime began making noises about the benefits of sanctions for Russian businesses in the months following their introduction, and it hasn’t stopped making them since. But what about the opinions of business people themselves? An RSPP poll found that large companies hold sanctions responsible for rising costs, the decreasing availability of credit, and lower volumes of investment. This belief is consistent with World Bank estimates: the volume of investment into the Russian economy – and particularly into the manufacturing sectors (which, given the depreciation of fixed assets in Russian industry, require it more than most) – is continuing to decline.

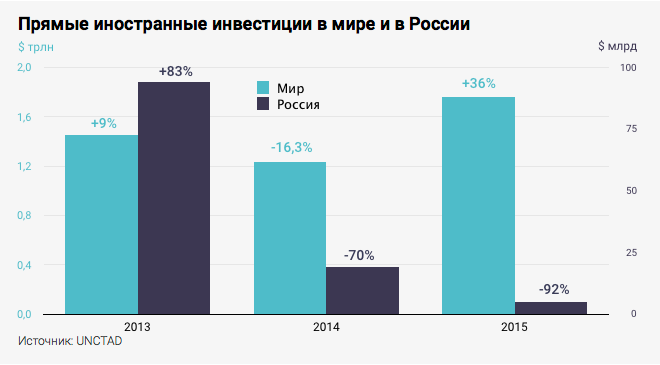

Foreign direct investment worldwide (in trillions of dollars) and in Russia (in billions of dollars)

2013 Worldwide +9%, Russia +84%

2014 Worldwide -16.3%, Russia -70%

2015 Worldwide +36%, Russia -92%

Source: UNCTAD

National economies have been fiercely battling over foreign direct investment (FDI) in recent years. FDI helps countries to create more jobs, implement the latest technologies and launch export projects. In 2009, despite a decrease in the total volume of FDI, Russia was among the top five recipients of FDI inflows. Still among the top 10 in 2012, it failed to make even the top 20 in 2015. US financial authorities’ insistent exhortations to stay away from Russia have had a considerable effect: major Western banks have refused to participate in the placement of Russian government debt securities. Even Asian investors, active all over the world, are choosing not to risk their position for the sake of a country slapped with sanctions by the global economy’s most influential players.

The last time Russia featured in the annually updated A.T. Kearney Foreign Direct Investment Confidence Index was back in 2013. Since then, global funds have, in most cases, been withdrawing their capital from the country, and even the Templeton Russia and East European Fund – one of the oldest investors in the Russian economy – deemed it best to cease their operations here.

This article was first published in Slon