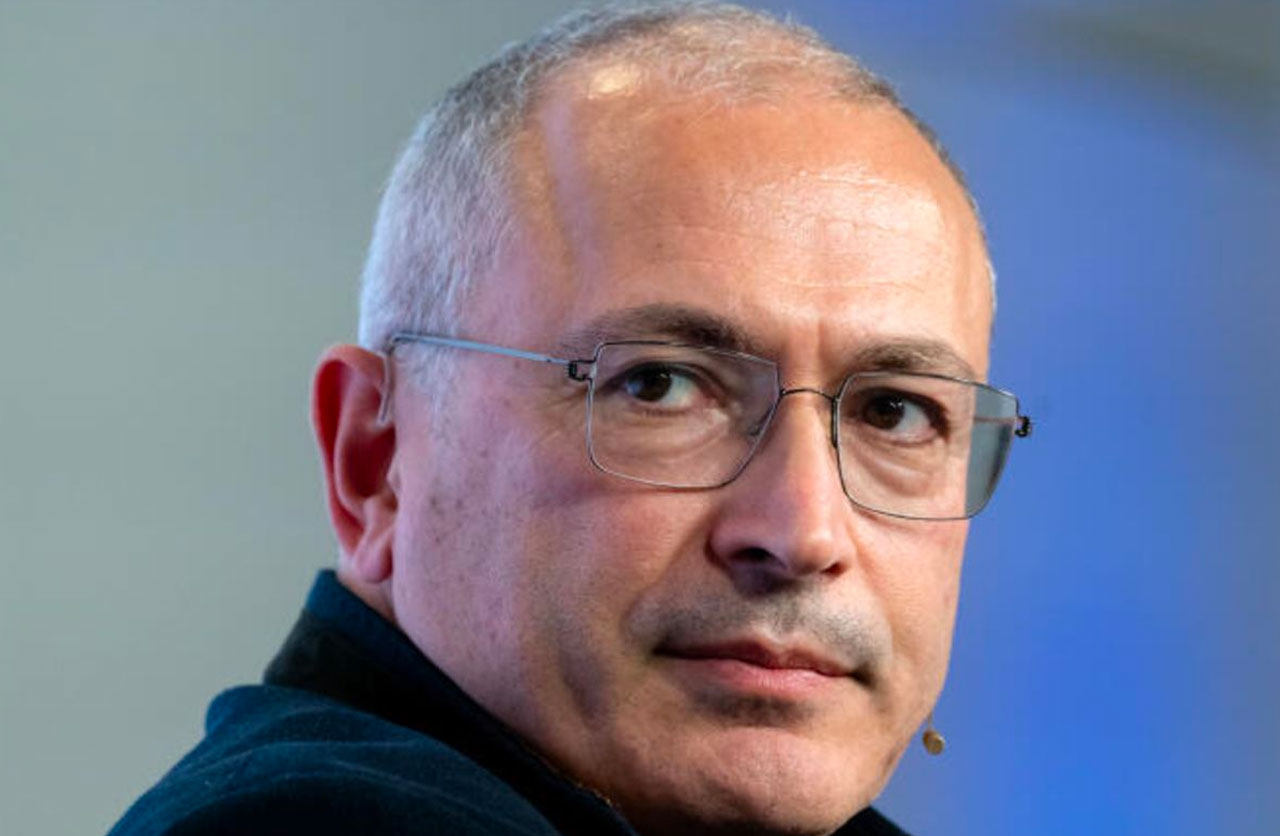

Newsletters / Mikhail Khodorkovsky on the stark lessons from Russia’s wild weekend

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

Yevgeny Prigozhin’s attempted coup was, despite its failure, a seismic moment for Russia, laying bare President Vladimir Putin’s vulnerability. As the mutiny unfolded, I suggested that Russia’s democratic anti-war opposition should welcome the opportunity that it presented, not because Mr Prigozhin is our friend or ally—a thug and war criminal, he is anything but—but because Mr Putin’s fall can only be brought about by force.

This was only the second time that Mr Putin has faced a truly revolutionary moment, the first being the mass protests of 2011-13. Yet back then, the democratic opposition was unable to capitalise. We need to wake up to the fact that the fall of the Putin regime and the creation of a better Russia will not come about through the ballot box or other peaceful means but will require armed insurrection. We can either be prepared for that or sidelined and eventually steamrollered by it.

Only an armed populace can topple this dictatorship. The nature of the attempted coup was not entirely unpredictable. Indeed, I have previously highlighted the risk to Mr Putin of the emergence of many thousands of aggrieved individuals in Russia, who now, as a result of his criminal invasion of Ukraine, have weapons, training and experience in using them. If and when Ukraine’s army penetrated the front, I argued, a horde of fighters retreating into Russia would threaten the regime in the way that the rollback of troops from the front in the first world war precipitated the Bolshevik takeover.

Had Mr Prigozhin succeeded, it is fanciful to think his coup would have brought about democratisation, the freeing of political prisoners and the calling of free and fair elections. If we in the democratic opposition wish to attain those goals then we must not only support the toppling of the regime but also be ready to assert our democratic interests through force when it falls. Our freedom at this stage will not be won by preparing for elections.

What the coup attempt made clear, however, is that Mr Putin is a lame duck whose days are numbered. It has dealt a potentially fatal blow to the legitimacy of his regime, in the eyes of both the Russian elites and society at large. He has been exposed as a weak leader, unable to control his inner circle and security forces and retreating into isolation when under threat. Far from being the master manipulator of divisions among those beneath him, he risks being toppled by forces he unleashed but can no longer control.

For the general population, the ease with which Mr Prigozhin’s mercenaries took over Rostov-on-Don, a city in southern Russia that serves as a key logistical staging-post for Russian forces in Ukraine, put paid to the idea that Mr Putin enjoys overwhelming public support. Russian elites, meanwhile, can no longer look to him as a guarantor of their status, stability and prosperity.

The president can no longer control his troops, and the population no longer believes the myths he peddles about his unnecessary, criminal war. Mr Prigozhin understood Mr Putin’s weakness, the parlous state of his war machine and the decimated morale of his troops. He wouldn’t have mutinied if he didn’t think he had a serious chance of success.

We glimpsed how the regime’s inevitable fall is likely to come about and the forces that will seek to take over—so called “national patriots” led by another thug. The democratic anti-war opposition and our natural allies in the West need to prepare for the regime’s collapse and cannot meekly allow the bandit currently in charge of Russia’s nuclear arsenal to be replaced by another.

The West should bet big on Russia’s democratic opposition and grant it agency, so that when the regime implodes we are capable of seizing the moment. Western powers should recognise our opposition institutions, such as the Russian Action Committee, as legitimate representatives of Russian society, enabling us to better compete with the militarised “national patriots” in the Prigozhin mould.

Simultaneously, there must be no let-up in the West’s support for Ukraine. It must continue to arm the Ukrainians to spur them on to victory. Mr Putin’s forces are in disarray and Ukraine must be fully backed to press home the advantage.

Within Russia, however, it is time to recognise that Mr Putin’s failure of a war has made his downfall inevitable. If the West wishes ever to see a Russia capable of being a responsible actor in the world, it needs to give its backing to the democratic anti-war opposition. The Russian opposition, meanwhile, needs to prepare for what comes next and the cold, hard reality that the next Russian revolution will not be of the velvet variety. The regime and the forces that will topple it will be armed. We may abhor Mr Prigozhin, but we cannot ignore that he has demonstrated the potential for successful sabotage against Mr Putin’s noxious regime.

Regime change is coming. Exactly when is impossible to say. But one thing is certain: we must be ready for it.

The article was first published in the Economist

In the media:

Khodorkovsky: Don’t Count On A Swift End To The War In Ukraine (Worldcrunch)

Khodorkovsky: The Future Of Russia — And Its Opposition (Politico Europe)

Putin in power will lead to the ‘disintegration’ of Russia, Khodorkovsky says

Change in regime is ‘far closer’ after Wagner Group rebellion, Putin critic says. Mikhail Khodorkovsky said opposition must prepare to exploit future uprisings.

Putin Won’t Resort to Nuclear Weapons for One Major Reason – Exiled Russian businessman and opposition activist Mikhail Khodorkovsky said that if Vladimir Putin resorted to nuclear weapons, his war effort in Ukraine could collapse “in several months.”

Get out of Russia while you still can, ex-oligarch warns Western energy giants

Mikhail Khodorkovsky speaks at the Cambridge Union Library

Mikhail Khodorkovsky on the war against Ukraine

Before and during the Zentrum Liberale conference “Russia and the West”, Mikhail Khodorkovsky spoke about the situation in his home country and the prospects for an end to the war of aggression against Ukraine.

BBC Newsnight

‘Putin’s dictatorship cannot be replaced except by violence or threat of violence’ Russia’s once-richest man and one of its most prominent dissidents Mikhail Khodorkovsky says what he thinks a change of power at the Kremlin would take

Conference THE DAY AFTER: Brussels dialogue – Roundtable of EU and Democratic Russia Representatives in the European Parliament

Michail Chodorkowski über Wagner-Rebellion: “Dieser Aufstand beschleunigt den Machtwechsel in Russland”

„Dieser Aufstand beschleunigt den Machtwechsel in Russland“

Nach dem Wagner-Aufstand gegen Putin: So reagiert Kremlkritiker Michail Chodorkowski

Michail Chodorkowski spricht über ein Russland ohne Putin

Khodorkovski: “Après celle de Prigojine, d’autres rébellions se produiront”

L’opposant Mikhaïl Khodorkovski : “La rébellion de Prigojine, une occasion unique de faire tomber le régime”

Mikhaïl Khodorkovski : “Vladimir Poutine n’est pas un dirigeant, c’est un bandit, il frappe d’abord et discute ensuite”

Khodorkovsky: «Usare la forza per abbattere Putin. La nostra opposizione deve essere pronta»