Other Victims

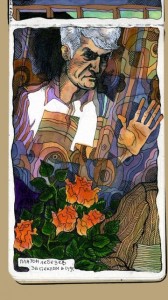

Platon Lebedev is a long-time friend and former business associate of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. On July 2, 2003, Lebedev was arrested straight from a Moscow hospital where he was receiving treatment, and he was detained and later imprisoned until his release over a decade later, on January 24, 2014. As a co-defendant with Khodorkovsky, Lebedev endured two show trials in which both men were found guilty and sentenced to identical prison terms. Lebedev was released only when the Presidium of the Supreme Court of Russia shortened his sentence to time served as of January 23, 2014, just over a month after President Putin released Khodorkovsky in December 2013.

BEFORE ARREST

Lebedev was born in Moscow on November 29, 1956. He graduated in 1981 from Moscow’s prestigious Plekhanov Institute of Economy with a degree in Industrial Economics. From 1981 to 1989, Lebedev was head of the economic planning department of Zarubezhgeologia, a company that traded in geological resources and acted as a chief contractor and chief exporter for the Soviet Union’s Ministry of Geology.

In 1989, Lebedev and his business partners, including Khodorkovsky, established Bank Menatep, one of the first commercial banks in Russia. Lebedev was president of Bank Menatep from 1991 to 1995. After establishing Bank Menatep, Lebedev and his partners founded Rosprom, a diversified holding company, and precursor of Group Menatep, which would eventually become the majority shareholder of Yukos.

In 1996, Lebedev became deputy chair of the executive committee of Yukos, and served as president of the company’s refining and marketing division from 1997 to 1999. As director and chair of Group Menatep, Lebedev’s responsibilities included investment strategy, due diligence, investor relations, accounting and financial reporting and legal compliance. He presided over the diversified holdings of Group Menatep and sought to make it a world-class company positioned for sustainable, growth-oriented business with international partners. Lebedev streamlined and optimised business operations and made finances transparent and compliant with high auditing standards. With the appointment of an International Advisory Board, Lebedev brought in eminent foreigners to assist in implementing international best practices of transparency and corporate governance. He also led efforts to introduce Yukos’s stock on international capital markets, and worked extensively with foreign financial institutions and investors in this regard.

AFTER ARREST

Lebedev’s successful business career came crashing down when he was arrested on July 2, 2003. Many perceived Lebedev’s arrest to be a warning to Khodorkovsky that he should flee the country. Khodorkovsky refused to go into exile, one of the main reasons being that he did not want to leave his friend and business partner Lebedev behind in detention.

First Trial

Lebedev’s first trial as co-defendant with Khodorkovsky began in June 2004. The defendants were subjected to grave injustices in the interpretation and application of Russian law, while the authorities concurrently pursued an attack on Yukos through the pretext of reassessments of the company’s tax payments. In May 2005, the Meshchansky Court of Moscow found both men guilty of almost every charge, sentencing them to nine years in prison. In September 2005, the sentence was reduced to eight years by the Moscow City Court in a ruling on an otherwise unsuccessful appeal by Khodorkovsky that also applied to Lebedev.

Lebedev was thereafter sent to a remote prison colony in the town of Kharp, on the Yamalo-Nenets Peninsula, above the Arctic Circle. The remoteness of the prison made it extremely difficult for Lebedev’s family and Moscow-based legal counsel to visit him.

Second Trial

With Lebedev about to become eligible in July 2007 for parole under Russian law, having served half of his eight-year sentence since his July 2003 arrest, new charges against him and Khodorkovsky were announced in February 2007. Proceedings were instigated ensuring that they would not be released on parole in 2007, or for that matter upon completion of their sentences in 2011.

A second trial against Lebedev and Khodorkovsky opened in Moscow’s Khamovnichesky Court in March 2009. A sham judicial process concluded with a guilty verdict in December 2010. Following a failed appeal in May 2011, their imprisonment was extended to 2016. Lebedev and Khodorkovsky are now serving combined sentences totalling thirteen years, counted from 2003.

The International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute had a full time observer at the second trial and concluded in their September 2011 trial observation report that the proceedings were not fair and were incapable of producing clear proof to sustain the verdict. Similarly, in December 2011 an official inquiry organised by then-President Dmitry Medvedev’s own human rights council identified serious and widespread violations of the law in the second trial, leading the council to call for an annulment of the verdict. Experts involved in the inquiry categorically rejected the court’s findings of illegality in Yukos’s operations and found no evidence proving allegations of embezzlement or money laundering.

From June 2011 to January 2014

From June 2011 to January 2014, Lebedev was an inmate at Penal Colony No. 14 in the town of Velsk, in the north-western Russian region of Arkhangelsk. Approximately 700 kilometres from Moscow, Velsk is surrounded by vast expanses of fields and forests and has been a place of political exile since the 1970s. The penal colony consists of two-storey brick barracks and the colony chief’s office building. There is also a shop where products made by prisoners are sold. Lebedev is allowed six visits per year. In contrast, at prisons of the same security level in the United States, prisoners are allowed visits every week.

Parole Application

On July 27, 2011, the Velsk district court rejected Platon Lebedev’s application for an early release on parole, despite Lebedev’s solid credentials, eight years served in detention, support from numerous witnesses and a petition for release signed by over one thousand people (read more).

A representative of the penitentiary administration opposed Lebedev’s eligibility for parole, arguing that Lebedev had been issued various reprimands over the past eight years, including for alleged impolite behaviour and for the loss of a pair of prison-issued trousers.

During the parole hearing, a letter from Lebedev’s 9-year-old daughter was read aloud, in which she pleaded with the judge: “I cry almost every day. I don’t sleep at night, thinking about papa. After all, time keeps moving on, and I am growing up…I hope papa will come back to us soon, after all he isn’t guilty of anything.”

At the close of the hearing, Lebedev highlighted three points to the judge: that it was unacceptable in 2011 for political prisoners to exist in Russia; that he was in need of treatment for chronic medical conditions; and that he had been deprived of being a husband, a father of four and a grandfather for longer than the two World Wars combined.

The judge refused to grant parole, citing the reprimands to impugn Lebedev’s suitability for release, and noting that Lebedev has refused to admit guilt.

In September 2011, British Prime Minister David Cameron visited Russia and met with Russian human rights activists to discuss civil society issues in Russia, including the Khodorkovsky-Lebedev cases. Dmitry Muratov, editor of the influential newspaper Novaya Gazeta, presented Cameron with a prison uniform, stating that the Velsk district court had refused to parole Lebedev on the pretext that he had lost just such a uniform. Upon returning to the United Kingdom, Cameron raised the Khodorkovsky case in his keynote annual speech on foreign policy, stating: “In September I was the first British Prime Minister to visit Russia for five years. Of course there are things on which I think Russia is in the wrong. The Litvinenko case. Magnitsky. Khodorkovsky. We can’t pretend these differences – of human rights, the rule of law – don’t exist. They do.”

Seeking Justice Abroad

With their appeals in Russian courts proving futile, during their decade in detention both Lebedev and Khodorkovsky submitted several applications to the European Court of Human Rights highlighting violations committed by Russian authorities in the proceedings against them.

Lebedev’s first application filed at the Strasbourg-based court concerned violations of his fundamental human rights in connection with his arrest and detention between 2003 and 2004, prior to his first trial. On October 2007 the European Court of Human Rights found that Lebedev had been detained illegally, that hearings were conducted without his attorneys or Lebedev himself present and that proceedings were repeatedly unlawfully delayed. Two years later, Russia’s Supreme Court conceded that Lebedev had indeed been treated illegally, but by then Lebedev was again facing prosecution in the second trial, and the Supreme Court’s ruling had no impact on those proceedings.

The calendar of rulings on Lebedev’s three other applications pending at the European Court of Human Rights has not been announced and cannot be reliably predicted.

AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL PRISONER OF CONSCIENCE

Since Lebedev and Khodorkovsky were arrested in 2003, Amnesty International has continually expressed concern over their treatment in detention. In May 2011, Amnesty International designated them both to be prisoners of conscience and called for their release. The position of Amnesty International echoes that of other international NGOs, including Human Rights Watch and Freedom House, as well as world leaders across the globe, in recognising the political nature of the prosecution of both men.

LINKS

Lebedev interview with the Financial Times, July 2011

Joint Khodorkovsky-Lebedev interview with Novaya Gazeta, October 2010

Lebedev interview with Novaya Gazeta, December 2008

Lebedev public appeal, March 2007

One of the most tragic human stories in the entire Yukos affair is the case of Vasily Alexanyan. With the Kremlin’s assault against Yukos well underway after the arrest of Mikhail Khodorkovsky in 2003, Harvard Law School graduate Alexanyan, former Yukos general counsel, stepped up in March 2006 to assume the position of Executive Vice President of Yukos. At the time the company was being forced through a state-orchestrated bankruptcy process. Alexanyan’s attempts to protect the company’s rights in this process were not tolerated by the authorities. After weeks of pressure, harassment, and repeated interrogations, Alexanyan himself was jailed on April 6, 2006.

Alexanyan was held in inhumane pre-trial detention conditions and deprived of medical treatment despite the fact that the authorities were aware that he was infected with HIV. He was repeatedly pressured to provide false testimony against Khodorkovsky in exchange for medical treatment, but he steadfastly refused. With a compromised immune system and lacking appropriate care in detention for almost two years, he became terminally ill with full-blown AIDS and lymphatic cancer. He died in October 2011 at the age of 39.

Blackmail and Torture

In January 2008, Alexanyan appeared before the Russian Supreme Court, stating that prosecutors had prevented him from receiving medical care as leverage to extort false testimony against Khodorkovsky. Alexanyan steadfastly opposed repeated attempts to blackmail him. As a result, he was kept in a damp basement cell where temperatures were as low as 5 degrees Celsius at night. In these horrific conditions Alexanyan developed full-blown AIDS and lymphatic cancer. His spleen had to be surgically removed. He suffered a near total loss of his vision. Meanwhile, without Alexanyan’s consent, in January 2008 a prosecutor publicly revealed Alexanyan’s HIV/AIDS diagnosis.

Alexanyan described in detail the blackmail that prolonged his detention and torture. At the January 2008 Russian Supreme Court hearing, he stated: “In the month of April [2007], investigator Khatypov – I’m naming names, because these people must one day be held responsible – says to my defender, who is present here: let him admit guilt, let him agree to the conditions and the procedure, and we’ll let him out. All this time, by the way, not only were they not prescribing medical treatment for me, they didn’t even want to take me out for repeat tests. This is torture, you understand, torture! Natural, legally authorised torture!”

Worldwide Outcry

The European Court of Human Rights repeatedly issued interim measures to the Russian authorities requesting that medical care be provided to Alexanyan. The authorities did not comply, leaving Alexanyan without anti-retroviral treatment for almost two years. The Court eventually ruled that Alexanyan’s treatment in detention “undermined his dignity and entailed particularly acute hardship, causing suffering beyond that inevitably associated with a prison sentence and the illnesses he suffered from, which amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment.”

Amnesty International called upon Russia to “provide all necessary medical treatment to Vasily Alexanyan, and investigate the failure of the authorities to provide him with prompt and appropriate medical attention” and further stated that “the denial of medical treatment to Vasily Alexanyan constituted cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.” (See Amnesty International documents published in January 2008, February 2008 and January 2009.)

French Foreign Minister Bernard Kouchner raised Alexanyan’s case in January 2008 directly with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov.

Russian civil society leaders, including Lyudmila Alexeyeva, Garry Kasparov and Boris Nemtsov, made appeals calling for Alexanyan’s release.

Beginning in late January 2008, Khodorkovsky went on a hunger strike, which he vowed to continue until receiving confirmation that Alexanyan had been transferred to a medical facility for treatment. The hunger strike lasted almost two weeks.

Release & Final Years

After intense international and domestic pressure, Alexanyan was finally transferred to a hospital in February 2008, nearly two years after his arrest. Despite being a seriously ill patient, and under heavy guard, Alexanyan was handcuffed to his bed. The manacle was hardly ever removed, except briefly to restore normal blood circulation. Even in hospital, Alexanyan was deprived of the optimal conditions of cleanliness and comfort, and of the full course of medical treatment, that would have been appropriate given his serious afflictions.

He was conditionally released nearly a year later, in January 2009, after paying $1.8 million for bail – a sum that Alexanyan was able to raise in large part thanks to an appeal to the public for help. The amount of funds demanded by the authorities for bail was unprecedented in Russia. Furthermore, Alexanyan had to prove to a court every four months that his medical condition continued to impede him from attending a trial. His conditions of release precluded him from seeking medical treatment abroad; however, Alexanyan had already been effectively sentenced to death.

Even after Alexanyan’s release, the authorities continued to pursue the case against him until it was finally dropped in June 2010, after four agonising years. He never fully recovered from the ordeal. On October 3, 2011, Alexanyan’s family reported to the media that he had passed away.

Alexanyan’s untimely death was not an accident, but rather the result of cruel and inhuman treatment he endured during a prolonged unlawful imprisonment that was part of the state’s attack on Khodorkovsky and Yukos. Alexanyan was survived by his parents and his ten-year-old son Georgy. Meanwhile, the architects of his tragic death are to this day free with impunity.

A Measure of Justice for Alexanyan through the Magnitsky Act?

The Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2011 is proposed United States legislation named after an anti-corruption lawyer who was also tortured and denied medical care in a Russian jail. Sergei Magnitsky died in detention in 2009, at the age of 37. The Magnitsky Act proposes international travel restrictions and foreign asset freezes targeted against a list of officials complicit in Magnitsky’s death and in other cases of grave human rights abuses in Russia. With the proposed legislation under consideration by the United States Senate Foreign Relations Committee, in early 2012 Russian human rights activists drew up an additional list, of officials complicit in Alexanyan’s death, with the goal of ensuring that these officials are targeted in addition to those on the Magnitsky list. Similar legislation aimed at Russia has been proposed elsewhere, including in Canada, the European Union and the United Kingdom.

LINKS

– Video and transcript of Alexanyan speaking to Russian Supreme Court

– Statements from Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Platon Lebedev

– A timeline of Alexanyan’s persecution

– List of those complicit in Alexanyan’s death

Yukos Victims

Russian investigators and prosecutors cast a wide net in attempting to secure statements and court rulings to be used in their proceedings against Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Filing more than fifty criminal cases against Yukos executives, employees, and others associated with Khodorkovsky or Yukos, the strategy of the Russian authorities has involved investigating or prosecuting business partners, juniors or even bystanders to obtain statements or court rulings that would produce “evidence” and establish “facts” as desired, negating the need for certain evidentiary proof or legal findings in prosecuting Khodorkovsky.

PARALLEL INVESTIGATIONS AND SECRET CASES

In pursuing Khodorkovsky, one of the prosecution’s favoured means of avoiding the obligations of due process – for example to circumvent rules on gathering evidence – has been the use of parallel investigations. Even if these parallel investigations never result in cases going to trial, they have provided opportunities for law enforcement authorities to employ alternative means to gather evidence to be used against Khodorkovsky, including through threats to others of criminal prosecution, detention and torture to extract false statements. Some of these parallel investigations were conducted for secret cases; others led to convictions in trials that should instead have been joined with the Khodorkovsky‐Lebedev proceedings.

WORLDWIDE RICOCHETS OF THE YUKOS AFFAIR

As a result of the brutal tactics employed by the authorities in pursuing Yukos-related investigations, many people were forced to leave Russia out of fear of persecution. The long arm of Russian justice has followed some of them abroad, for example through the issuance of extradition requests. These actions are part of the authorities’ attempt to portray Yukos as an organised criminal group, to justify the prosecution of Khodorkovsky and the expropriation of the company. However, it has been clear to the international community that Russia’s actions against Yukos-connected individuals have been politically motivated. Russia’s extradition requests and attempts to gain assistance from foreign law enforcement authorities in chasing Yukos-connected individuals have repeatedly failed.

WIDER IMPACT ON RUSSIAN ENTERPRISE & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The artificial criminalization of legitimate entrepreneurial activity by corrupt state officials now constitutes a major restraint on economic growth and modernisation in Russia. Since 2003, a group of powerful and corrupt figures in Russia developed and honed corporate raiding methodologies in the course of their treatment of Khodorkovsky and the forced bankruptcy of Yukos. These methodologies have been replicated throughout Russia by other state officials who take their cues from the very public handling of the Yukos affair.

The raiding of private businesses by corrupt Russian state officials, exemplified by the treatment of Khodorkovsky and Yukos, has created a regime of impunity in which the violation of people’s fundamental rights is “business as usual”. One in six Russian businessmen has been on trial and approximately one-fourth of the 900,000 inmates in Russian jails in 2010 were entrepreneurs, accountants, legal advisers, and mid-level managers – many of whom were victims of abuse of the criminal justice system through fabricated cases (read more). Entrepreneurs pay heavily in bribes to bureaucrats and other representatives of this corrupted “new nobility” (read more).