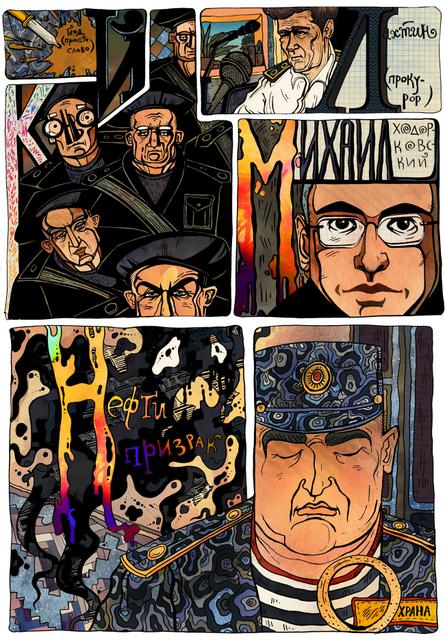

Second Trial (2009-2010)

In 2007, Mikhail Khodorkovsky and his business partner Platon Lebedev became eligible for release on parole under Russian law, having served half of their eight-year sentences since being arrested in 2003 and convicted in a politically-driven first trial that ended in 2005 – while Yukos was destroyed through bogus tax reassessments, forced bankruptcy proceedings and rigged auctions. Given their eligibility for release on parole in 2007, or at the latest upon completion of their eight-year sentences in 2011, new charges were sloppily manufactured and proceedings were instigated against Khodorkovsky and Lebedev to prevent their release. The new charges, announced in February 2007 and brought to Moscow’s Khamovnichesky Court in a second trial that started in March 2009, were intended to keep Khodorkovsky and Lebedev isolated from Russian political and business spheres, to stain their reputations and to whitewash and distract attention from corrupt and criminal actions committed by high-ranking Russian officials, many of whom are believed to have personally benefitted from the destruction of Yukos. Khodorkovsky and Lebedev were found guilty in December 2010. Following a failed appeal in May 2011, their imprisonment was extended to 2016, precluding their release in 2011 upon completion of their initial eight-year sentences.

Following a relentlessly absurd saga of appeals their sentences were reduced by two years when an appeal hearing finally took place at the Moscow City Court on December 20, 2012. The reduction was due to 2011 changes to Russian sentencing guidelines. Despite the enormous weight of legal and factual arguments undermining it, the appeal judges confirmed the December 2010 guilty verdict. Incredibly, the ruling lacked any thorough judicial analysis of the appellants’ arguments.

Click here to read “Justice Under Pressure – The Second Khodorkovsky-Lebedev Trial – Executive Summary”

CHARGES

PRE-TRIAL INVESTIGATION

After the allegations were formally presented in 2007, Khodorkovsky and Lebedev made consistent efforts to engage with investigators and prosecutors in good faith and in compliance with procedural rules. In contrast, the investigators and prosecutors consistently acted outside of the boundaries of the law. The basic duties of the investigators and prosecutors – to investigate relevant facts and to build a case grounded in law or to terminate a case where no actionable crimes exist – were unfulfilled. By January 2009, the quantity and severity of the investigators’ procedural abuses against the backdrop of bafflingly nonsensical evidentiary and legal grounds led the defense to request that the case be terminated as incurably flawed. The request was rejected by the procuracy and the case was sent to trial. In March 2009 Khodorkovsky and Lebedev petitioned Judge Viktor Danilkin of Moscow’s Khamovnichesky Court to terminate the proceedings. The court rejected the petition and the trial’s opening hearings commenced that month.

PROSECUTION’S CASE

The prosecution’s presentation of its case ran from April 2009 to March 2010. Despite filling time by reading from a 188-volume case file, and parading numerous witnesses into court, prosecutors were unable (and did not even try) to prove how it was possible that Yukos covered its operating costs, invested heavily in capital expenditures and acquisitions and paid taxes and dividends when the entire oil production of Yukos over a six-year period was being stolen, as alleged in the indictment. The prosecution’s witnesses proffered either no testimony germane to the accusations, or testimony that actually contradicted the accusations. Despite having over 11 months to read documents and question witnesses in court, the prosecutors plainly failed to prove their charges. This did not prevent prosecutors from proclaiming in their closing arguments that they had proven the guilt of the defendants – while being unable to sum up precisely how they supposedly did so.

DEFENCE DEPRIVED OF MEANINGFUL DUE PROCESS

In the face of official misconduct and due process violations, as the trial unfolded the defence presented highly substantiated motions for the recusal of prosecutors and of the judge – to no avail. Appearances of an adversarial trial were for the most part cosmetic efforts by the authorities to portray the process as legitimate. The defendants were permitted to speak in court almost without restrictions, but the judge blocked their lawyers from introducing exculpatory documentary evidence and refused to hear many witnesses and experts. The defence was allowed to file motions and objections, but the vast majority of these motions and objections were routinely denied or ignored. These motions and other defence pleadings were posted online by the defence, along with English translations, illustrating the absurdities of the process that was unfolding.

The “case-closed” mentality of the prosecutors ultimately reigned in the courtroom, given the judge’s biased handling of the multitude of due process violations that marked the proceedings. The defence’s protestations over the contradictions and outright irrationality of the case were brushed aside by prosecutors and the judge, who refused to address these issues directly. Independent observers visiting the trial described the proceedings as evocative of the works of Kafka and Gogol and an embarrassment to Russia.

Nevertheless, despite each successive setback, the defendants made every effort to engage with prosecutors and the court, and they presented a vigorous, methodical, and meticulously substantiated defence from April to September 2010.

Irrespective of the efforts of the defence, which were notably bolstered by the candour of former and current government officials who supported the defendants through in-court testimony, the proceedings continued to be undermined by unfair and unlawful decisions and manoeuvres that irreparably frustrated Khodorkovsky’s and Lebedev’s rights to a fair trial. A feeling of futility reigned in the courtroom as the defence presented its closing arguments in what had become a mock judicial process devoid of meaningful adversarial engagement on the substance of the case.

The reading of the verdict was initially scheduled for December 15, 2010 but a note posted on the courtroom door that day announced a postponement to December 27, 2010. The next day, December 16, 2010, then-Prime Minister Vladimir Putin publicly intervened in the case during his annual nationally televised question-and-answer session. With the judge still deliberating on the verdict, the Prime Minister cited the embezzlement charges, claimed that Khodorkovsky’s guilt had been proven in court, and stated: “A thief must sit in jail.” (read more). This was not the first time that Putin had publicly made defamatory statements about Khodorkovsky. The timing of this particular remark obviously signalled the expected outcome of the trial.

On December 27, 2010, Khodorkovsky and Lebedev were declared guilty of embezzling and laundering the proceeds of all oil produced by Yukos subsidiaries over a six-year period. The court found the defendants guilty of having embezzled significantly more oil than prosecutors had alleged. The prosecution’s sudden announcement during the trial’s closing arguments that they were reducing by approximately one third the volume of oil allegedly embezzled – perhaps a last-minute bid for a modicum of credibility – was ignored by the judge. Indeed, a comparison of the indictment and the verdict reveals that the judge simply copied vast tracts of the indictment, verbatim, into the verdict (see page 56 and the Appendix of an analysis of the verdict prepared by Jeffrey Kahn for the Presidential Council of the Russian Federation for Civil Society and Human Rights).

The 689-page decision is a hodgepodge of texts setting forth unsupported factual and legal assertions that fail to validate the finding of guilt. The document is marked by obvious errors of fact and of law, unsupported leaps of logic, internal incoherencies, and major inconsistencies with the findings of other cases adjudicated by the Russian courts. Despite the closely watched nature of the case surrounding the most high-profile prosecution in Russia, in the decision the court disregarded applicable procedural and substantive laws as well as fundamental tenets of economics, established facts and common sense.

In convicting the defendants of massive embezzlement, the court notably ignored both the uncontested profitability data of Yukos’s production subsidiaries, and the true market prices of oil in Russia. The court thus avoided proof of the absence of the harm that would have had to have been suffered for the embezzlement charges to have any validity.

Sales of oil by the subsidiaries to Yukos trading companies were deemed to constitute embezzlement simply insofar as the oil was sold at a price less than the export spot price. This concocted theory of embezzlement ignored market pricing in Russia as well as industry-standard, lawful procedures for corporate functioning undertaken by Yukos, involving a downstream and upstream structure of production subsidiaries and domestic and foreign operating companies. Rather than referring to openly verifiable historic domestic prices for Siberian oil, the verdict ascribed the Rotterdam price to domestic transactions, in order to argue that the much higher Western price ought to have been applied. This ignored transport costs, customs duties and other expenditures that make up the difference between the price of oil in Siberia and the price of oil in Rotterdam. The verdict simply brushed away these realities, with the judge stating that he did not agree that oil prices differ on domestic and global markets.

On December 30, 2010, with less than a year remaining before completion of their existing prison terms, Khodorkovsky and Lebedev were sentenced to an overall total of 14 years in captivity, later reduced by one year on appeal.

LEGAL CONTRADICTIONS

The verdict contradicted prior Yukos cases in Russian domestic courts, as well as the Russian Federation’s lines of defence in Yukos‐related proceedings abroad.

The punitive taxes that bankrupted Yukos were validated in Russia by numerous rulings in cases brought before the courts. In those cases the structuring of Yukos transactions with production subsidiaries was scrutinized and judicially approved. The determination of who owned Yukos oil was also recognized by the courts: according to all other courts in Russia, Yukos owned and sold that oil, and Yukos was therefore subject to taxation of its resulting revenues. Leaving aside arguments over the unfair and irrational punitive taxation of Yukos, these court decisions nevertheless stand today as Russian jurisprudence that cannot, under Russian law, be contradicted by inverse logic in other court rulings. The new criminal allegations against Khodorkovsky and Lebedev therefore created a juridical paradox: either Yukos owned and sold the oil, a legally settled fact under Russian law as determined by all previous courts; or Khodorkovsky and his alleged co‐conspirators embezzled the oil, in which case it could not have also been sold and taxed by Yukos. In finding Khodorkovsky and Lebedev guilty, the court created a massive and irreconcilable contradiction with an entire set of standing judgments.

At the European Court of Human Rights, a claim for unlawful expropriation was brought against the Russian Federation by former executives of Yukos, not involving Khodorkovsky or Lebedev (see “Yukos at the European Court of Human Rights”). In those proceedings, the Russian Federation defended the legality of punitive taxes on oil they asserted was owned and sold by Yukos, claiming that Russian tax authorities made punitive re‐assessments of Yukos on the basis that oil bought by Yukos trading companies “in fact” belonged to Yukos. As a result, Yukos was assessed to corporate profit tax as if it, and not the trading companies, had made the trading companies’ profits. Because of the tax authorities’ assertion that Yukos was the owner of the oil produced by Yukos production subsidiaries, the company was further charged value added tax on export sales that would have normally been exempt. Simultaneously however, in the criminal proceedings against Khodorkovsky and Lebedev, the verdict concluded that the same oil was not owned by Yukos but rather stolen from the company’s production subsidiaries by the defendants, who were accused of physically embezzling at the wellhead. The incompatible positions – one version for the European Court of Human Rights and a different version for the Khamovnichesky Court – were thus absurdly argued concurrently on behalf of the Russian Federation in major parallel proceedings.

POST-TRIAL REVELATIONS

In an interview with Gazeta.ru released in February 2011, Natalia Vasilyeva, an aide to the trial judge and press secretary of the Khamovnichesky Court, spoke out about the verdict. Vasilyeva stated that the trial judge’s first draft of the verdict had been reviewed and rejected by outside judicial officials, of the higher-level Moscow City Court, who replaced the text with their own. She also stated that the trial judge had to consult with those officials throughout the two‐year trial. The Economist described Vasilyeva’s widely‐reported comments as “explosive”, and quoted her as saying that “everyone in the judicial community understands perfectly that this is a rigged case, a fixed trial.” (read more).

Then, in April 2011, a second official who worked at the court during the trial corroborated Vasilyeva’s account (read more). Igor Kravchenko, a former court administrator, stated in an interview with Novaya Gazeta that the trial judge, speaking about the Khodorkovsky‐Lebedev case, had admitted: “I don’t decide this.” Referring to outside judicial officials at the Moscow City Court who had no lawful basis to interfere in the trial outcome, the trial judge was quoted by Kravchenko as having said: “Whatever they say, that’s what will be.”

APPEALS

The appeal was heard by the Moscow City Court – and rapidly dispensed with in a ruling on May 24, 2011 that confirmed the lower court’s guilty verdict, although the sentencing was reduced by one year. Khodorkovsky and Lebedev are now scheduled for release in 2016, on the 13th anniversaries of their respective arrests.

Khodorkovsky and Lebedev did not expect a fair ruling from the Moscow City Court, given that it was this same higher-level court that was widely seen as having been ultimately in control of the proceedings in the court of first instance. Moreover, the Moscow City Court’s chair, Olga Yegorova, is reputed for doing the Kremlin’s bidding in politically sensitive cases, and for having purged dozens of independently minded judges from the bench. Yegorova, married to a general of the KGB’s successor FSB, also oversaw the first Khodorkovsky-Lebedev trial and unlawfully allowed second trial investigations to be displaced to Siberia. She has spoken out in the news media to oppose criticisms and stand behind the handling of the Khodorkovsky-Lebedev proceedings.

Khodorkovsky and Lebedev lodged a supervisory appeal against the Moscow City Court’s May 2011 ruling. The supervisory appeal was rejected by the Moscow City Court in November 2011. The same court rejected a subsequent supervisory appeal against the November 2011 decision in January 2012. Khodorkovsky and Lebedev then filed a supervisory appeal at the Russian Supreme Court, in February 2012, which in turn was rejected in a May 2012 ruling. Oddly, that ruling was signed by a single Russian Supreme Court judge who is a military judge.

After a two-year appeal process, on December 20, 2012, the Moscow City Court upheld the guilty verdict handed down at the end of the second trial of Khodorkovsky and Lebedev in December 2010, although sentencing was reduced from 13 years to 11 years due to the application of recent amendments to Russian law. If the ruling stands, Khodorkovsky is to be released in October 2014 instead of October 2016, and Lebedev is to be released in July 2014 instead of July 2016. Khodorkovsky’s defence lawyer Vadim Klyuvgant commented: “The position of the defence team remains the same: our defendants are innocent and should be released immediately.”

Khodorkovsky’s defence team filed another appeal to the Russian Supreme Court in February 2013. It took the Supreme Court until May 2013 to announce that it would hold an appeal hearing on August 6, 2013. It also specified that only a small part of the December 2010 verdict, and not the guilty verdict itself, will be subject to review.

Despite the apparent futility of pursuing these appeals to regain their freedom, Khodorkovsky and Lebedev were determined to continue exposing the lawlessness of the proceedings they endured, and to highlight the disregard for the rule of law in Russia that has infected not only their own cases but also those of thousands of others.

Click here for more information about Khodorkovsky’s past prison conditions.